April 3, 2013 – As lawmakers prepare the state budget, the State Bar of Wisconsin encourages restored state funding for free or reduced-fee legal services that will help the state’s poor when facing civil matters with life-altering consequences.

Funding helps legal service providers deliver free or low-cost legal services in civil cases to the poor, including to veterans, victims of domestic violence, the elderly, disabled, and children and families. Currently, these agencies are funded by Wisconsin lawyers, federal and private grants.

In 2011, the Wisconsin Legislature completely eliminated general purpose state funding for civil legal services, making Wisconsin one of just four states to do so.

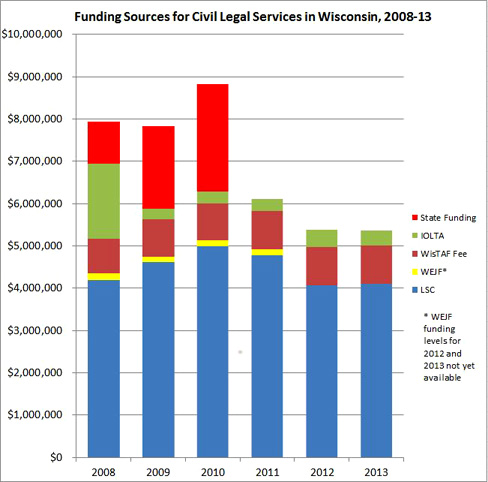

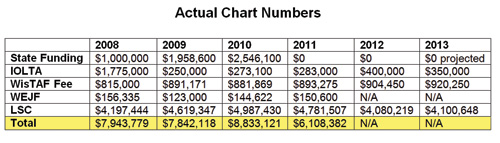

Previously, the state made a $1 million appropriation for civil legal services in 2008, a $1.9 million appropriation in 2009, and a $2.5 million appropriation in 2010.

Although there’s a projected $420 million surplus for fiscal years 2013-15, Gov. Scott Walker’s proposed budget does not restore civil legal service funding.

Without adequate funding for legal services, more vulnerable citizens are forced to represent themselves in serious civil matters, which can negatively impact the outcomes of their cases as well as the court system’s ability to administer justice efficiently.

Pro bono lawyers and programs, law school legal clinics, self-help centers, and modest means initiatives are attempting to bridge what’s known as the “access to justice” gap.

In 2012, Wisconsin lawyers in private practice donated over 100,000 hours of free legal services to the poor, according to Jeff Brown, the State Bar's pro bono coordinator. But even these volunteer efforts cannot bridge the widening access to justice gap.

The Wisconsin Access to Justice Commission – charged with developing new ways to expand access to justice for the poor – continues to explore new funding sources. But state funding is a crucial aspect to a multi-pronged funding approach.

“The state should be a partner with the philanthropic and legal communities, which put a lot of time and money into the system,” said Gregg Moore, president of the 17-member Access to Justice Commission.

The State Bar of Wisconsin has long supported adequate state funding for civil legal services. In 2009, it successfully petitioned the Wisconsin Supreme Court to create the Access to Justice Commission, which is funded by State Bar members.

Funding for Civil Legal Services Decreases

Lawyers fund free and low-cost civil legal services directly through a supreme court assessment, currently $50, payable annually to Wisconsin Trust Account Foundation (WisTAF). WisTAF is the state’s largest private funding source for civil legal services.

In addition, interest on lawyers’ trust accounts (IOLTA) is directed to WisTAF, which also administers private donations made to the Wisconsin Equal Justice Fund.

Joe Forward is the legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin. He can be reached by email at jforward@wisbar.org or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

Low interest rates caused IOLTA funding to decrease by almost 70 percent in 2009 – from $1.77 million in 2008 to $250,000 in 2009 – and 2009 levels have only increased slightly. WEJF donations averaged about $144,000 per year from 2008 to 2011.

In 2011, WisTAF distributed $1.3 million to 16 civil legal service providers across Wisconsin, 65 percent less than the $3.7 million it was able to distribute in 2010 with a state appropriation of $2.5 million for civil legal services.

In addition, the federal Legal Services Corporation (LSC) helps fund Legal Action of Wisconsin and Wisconsin Judicare, the largest civil legal service providers in the state.

Legal Action, which serves 39 southern Wisconsin counties, has 55 paid lawyers and 50 paid staff members. Judicare, which serves 33 northern counties and 11 federally recognized Indian tribes, employs seven staff lawyers and 11 staff members.

In 2012, those organizations received a combined $4 million from LSC, a 19 percent drop since 2010. Amidst economic downturn, LSC cut funding by nearly 14 percent for the 2012 fiscal year. Another 7.4 percent is estimated to be cut through sequestration, according to De Ette Tomlinson, WisTAF's executive director.

Both nonprofit firms run volunteer programs, soliciting pro bono help from private lawyers. In the past, Judicare has also paid private lawyers $45 per hour to assist with cases.

But as funding runs dry, Judicare can’t pay for the outside help. Rosemary Elbert, executive director of Wisconsin Judicare, says funding cuts have forced the organization to restrict the number of outsourced cases in the last two years.

In addition, the organization has been forced to drastically limit the number of cases it can accept. In 2012, Wisconsin Judicare received 4,260 applications for services. Of those, only 2,146 (50 percent) were eligible based on stricter eligibility requirements.

“Reduced funding has forced us to strictly limit our financial eligibility requirements to individuals within 125 percent of the federal poverty guidelines,” Elbert said.

Previously, Judicare accepted individuals within 200 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. Based on 2013 guidelines, an individual will not currently qualify for Judicare’s legal services if his or her income exceeds $14,362 ($7.48 per hour). A couple with a small child would not qualify for services if income exceeds $24,412.

“The impact on services is incredibly grim,” said Tomlinson at WisTAF, which manages and distributes funding grants, including funds received from LSC. “Basically, only the poorest of the poor are currently getting help.”

Unmet Legal Needs Growing

Unmet Legal Needs Growing

In 2000, an estimated 70 percent of family law cases involved at least one pro se litigant. In 2007, the State Bar reported that more than 500,000 indigent Wisconsin citizens faced at least one significant legal problem per year without legal assistance.

“My hunch is that those numbers are much higher now,” said Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Rick Sankovitz. “For one, reduced funding means fewer lawyers to provide services to the indigent. And because of dislocations in the economy, more people are coming to court on the types of cases where you typically see pro se litigants.”

Those cases often involve family law, housing, health care, long-term care, disability, and public benefits – cases often involving the state’s most vulnerable individuals.

In 2011, more than 30 percent of WisTAF-funded cases involved health issues, long-term care or disability. Another 27 percent involved housing or family law, including victims of domestic or spousal abuse who are trying to escape the situation.

“Every day, Wisconsin residents who face important legal problems are forced to go it alone in court, before government agencies, and in negotiations,” said former State Bar President John Skilton in a video released by the Access to Justice Commission.

“Sometimes they just give up because they can’t afford the help they need, and they can’t effectively represent themselves,” said Skilton, who is also the former chair of the American Bar Association’s Commission on the Delivery of Legal Services.

An estimated $30 million is needed each year to meet the needs of the state’s low-income families, WisTAF reports. In 2013, without state funding, Wisconsin’s legal service providers will share about $5.5 million, almost 30 percent less than 2010.

Shirley Abrahamson, chief justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, recently asked lawmakers to include an “access to justice” appropriation in the budget.

“I am concerned for indigent individuals who find themselves in court without counsel in high-stakes cases,” she told the legislature’s Joint Committee on Finance.

“The result is that individuals in our communities, without legal assistance, struggle to stay in their homes, to keep their children, to get government benefits, or to protect themselves from abusers,” the chief justice said.

How Can State Funding Help?

According to judges and lawyers, two distinct problems arise when there’s inadequate funding to support civil legal needs for low-income individuals.

First, those who can’t afford to pay for a lawyer’s legal services often represent themselves without adequate knowledge of law or legal procedure.

Secondly, pro se litigants strain limited court resources. The judicial system, a co-equal branch of government, operates on less than one percent of the state’s total budget, as the chief justice noted in her testimony before the Joint Finance Committee.

Self-represented litigants often require extra help from court staff on common practices and procedures. At the same time, courts have obligations to remain neutral.

“So many times, judges are forced to sit at our neutral posts, watching as untutored parties self-destruct, watching as one side takes advantage of the naiveté of the other,” Judge Sankovitz said. “Making lawyers available in these cases would restore a good deal of confidence on the fairness of proceedings in our courts.”

In addition, judges must spend inordinate amounts of time deciphering pleadings, briefs, or other arguments by untrained pro se litigants. “Circuit judges definitely would support restoring the funding for civil legal services,” Sankovitz said.

Unlike criminal defendants, civil litigants don’t have a right to counsel, though civil matters often involve evictions or disability benefits with food or shelter on the line. Previously, state funding helped more Wisconsin citizens get access to lawyers.

“Those funds put lawyers directly to work in cases such as landlord-tenant disputes, where homelessness can be at stake,” Sankovitz said. “They supplied lawyers for divorcing couples where the stakes are extremely high for the kids in our communities.”

Judges have inherent authority to appoint counsel in civil cases. But currently, funding could not regularly pay for the legal services necessary for such appointments.

“So many people who can’t afford lawyers can’t get the guidance they need just from the forms we help them fill out to get started with their cases,” Judge Sankovitz said. “Many need advocates, planners, and professional know-how to learn their rights and avoid squandering them through mistakes that one might expect of nonlawyers.”

As lawmakers consider a state budget for 2013-15, Gregg Moore notes that more resources are necessary to meet the legal needs of Wisconsin’s citizens.

“The need is great. The need is getting greater all the time,” he said.