In 2000, the Wisconsin Legislature joined a national trend by creating a presumption of joint legal custody and greater parity in physical placement time in family law cases involving children.1 After the passage of 1999 Wis. Act 9, the statutes directed courts to nominally consider the best interests of the child when awarding legal custody; however, the newly passed legislation also created a presumption that “joint legal custody is in the best interests of the child.”2

This change alarmed domestic abuse victims and their advocates and lawyers. They believed this presumption would result in more joint custody arrangements for families, exposing victims and their children to ongoing control and abuse after separation. The legislation also directed courts to maximize physical placement for each parent. Many people believed the emphasis on joint decision-making would force victims and children into more contact with abusive parents.

Statutory Presumption Regarding Effect of Domestic Abuse

In response to these concerns, the state legislature passed 2003 Wis. Act 130, which created a rebuttable presumption that when one party has engaged in a pattern or serious incident of interspousal battery, joint or sole custody to the abusive parent is contrary to the child’s best interest.3 In these cases, the “safety and well-being” of the abused parent and child become “paramount concerns” when determining custody and placement, even if the custody presumption is rebutted.4

Tess Meuer, U.W. 1983, recently retired as justice systems director after 24 years at End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, Madison.

Tess Meuer, U.W. 1983, recently retired as justice systems director after 24 years at End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, Madison.

Tony Gibart, U.W. 2009, is the associate director at End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin.

Tony Gibart, U.W. 2009, is the associate director at End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin.

Adrienne Roach, Brandeis Univ. MA 2013, is the organization’s policy and systems analyst.

Adrienne Roach, Brandeis Univ. MA 2013, is the organization’s policy and systems analyst.

Regarding placement, Act 130 directs the court to “provide for the safety and well-being of the child and for the safety of the party who was the victim of the battery or abuse” and to “impose” one or more enumerated safety conditions “as appropriate.”5 Victims and their advocates hoped these and other provisions of Act 130 would counter the overall trend toward joint legal custody and more equalized physical placement in domestic abuse cases.

Although expected to do so, the passage of Act 130 did not alleviate concerns about custody and placement orders in cases involving domestic abuse.6 End Abuse consistently hears about the ineffectiveness of Act 130 from advocates and family law attorneys. Many lawyers adhere to the notion that divorcing spouses must learn to cooperate. Thus, they might not see the relevance of raising the issue of domestic abuse, explain domestic violence presumptions to clients, or, for fear of “rocking the boat,” present evidence of domestic abuse to the court.

Study of Family Law Cases Involving Domestic Abuse

To better understand what drives the custody and placement outcomes of cases involving domestic abuse, End Abuse researched cases with criminal convictions for domestic abuse felonies or misdemeanor battery. These cases were chosen not from a belief that parents who commit serious acts of domestic abuse are always convicted; rather, these cases involved families with a known domestic abuse history, forming an optimal sample of cases.

The data is limited to documented outcomes as reported in case files. Information regarding the desired outcomes of the parties involved is not included. The research aimed to learn how criminal histories of domestic violence generally affect documented family law outcomes in the wake of Act 130, not to draw conclusions about specific cases.

Because all examined cases involve a documented history of domestic abuse before the divorce filing, researchers expected to find that prior adjudication of domestic abuse by one parent against the other would result in outcomes more likely to reflect the provisions of Act 130 and domestic abuse dynamics.

Specifically, researchers expected to find:

-

Formal domestic abuse findings in more than one-half of cases reviewed;

-

Guardian ad litem (GAL) recommendations of sole custody and at least primary placement with the victim in more than 75 percent of cases;

-

Final orders resulting in sole custody with the victim in more than 75 percent of cases;

-

Final orders resulting in at least primary placement with the victim in more than 75 percent of cases; and

-

Final orders including at least one safety provision in more than 75 percent of cases.

Despite the rarity of formal findings, most cases should result in sole legal custody and primary placement to the victim, with safety provisions. Analysis suggests Act 130 does not have this effect.

Data Collection and Analysis Parameters. Because of resource constraints, data was collected in some but not all Wisconsin counties. To ensure an unbiased, representative dataset, 20 counties were randomly selected by population size, representing each judicial district. Higher population counties had a greater probability of selection, but random selection ensured smaller counties were also included.

Data collectors studied every divorce action involving children from 2010 to 2015 in which a court convicted one parent of a domestic abuse crime against the other parent within five years after the final order. Due to search limitations, researchers could only match family law cases with criminal convictions in the same county. These cases were matched with criminal convictions from 2008 to 2015. The data include convictions for felonies and misdemeanor battery; lesser convictions are not included. This study found 361 such cases in which the victim and the defendant had children in common.

Key Findings of Study

Domestic Abuse Findings Are Rarely Made. Under Act 130, a court finding that one party engaged in a serious incident or pattern of interspousal battery or domestic abuse triggers the presumption that joint custody is not in the best interest of the child, whereupon the safety of the children and victim is a paramount concern in deciding custody and physical placement.7 The law requires a finding of domestic abuse: these 361 cases contain previous convictions of no less than battery. Therefore, researchers expected findings in at least 50 percent of cases because the statutory factual predicates for the application of Act 130 were very likely in place for most if not all cases.

However, only 29 cases (8 percent) had a domestic abuse finding, likely because most family law cases are resolved before trial. In over 80 percent of cases, litigants reached stipulated agreements. Victims stipulate for many reasons. Some stipulate because they reached an acceptable solution with the other party. Others stipulate because they feel pressure to accept a GAL’s recommendations, or they lack the legal knowledge and resources necessary to continue to trial.

Act 130 is not widely producing placement orders that explicitly attend to safety.

Joint Custody is the Most Common Order. In cases in which serious, documented domestic abuse occurs, Act 130 is designed to keep the victim and their children safe by presuming that sole legal custody should be awarded to the victim. Even if most cases are resolved without a domestic abuse finding, one would expect Act 130 to affect custody and placement outcomes as parties negotiate settlements.

Meet Our Contributors

Why do you do what you do? What's the best advice you ever received? Share your weirdest courtroom story...

Lawyers have a lot to say. Our authors are no exception. Whether its personal, insightful, or fun, it’s always interesting.

Check out our Q&A with the author below

Theoretically, family law litigants, knowing that Act 130 provisions apply, will tend to negotiate settlements that reflect the legislation’s intended outcomes: sole legal custody to the victim and safe placement arrangements. Therefore, despite the rarity of formal findings, most cases should result in sole legal custody and primary placement to the victim, with safety provisions. Analysis suggests Act 130 does not have this effect.

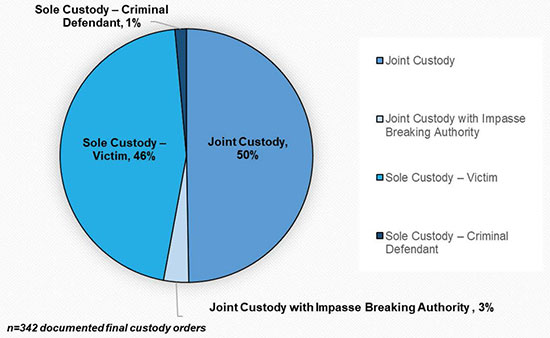

Researchers expected at least 75 percent of final orders to result in sole custody. Instead, 50 percent of cases resulted in joint custody. When impasse-breaking authority is included, it increased to 53 percent. These percentages are based on all known custody outcomes. Of the 361 cases reviewed, the custody order was documented in 95 percent of cases. (See Figure 1, Frequency of Court Decisions on Child Custody.)

Recognizing the effect incarceration could also have on custody and placement outcomes, file reviewers noted whether the abuser was in prison. When the abusive parent was not in prison, the court orders for joint custody increased to 62 percent of cases.

In the 135 cases with a GAL, there were approximately as many orders of sole custody as there were of joint custody (including joint custody with impasse-breaking authority). Of the 135 cases with a GAL, 127 had documented custody outcomes.

When the abusive parent was not incarcerated, and a GAL was involved, the percentage of joint custody orders (including five orders with impasse-breaking authority) increased to 63 percent. Of the 135 cases with a GAL, the abuser was not in prison in 82 cases (61 percent); custody outcomes were documented in 78 of these cases. The court ordered joint custody in 44 cases and joint custody with impasse-breaking authority in five cases.

File reviewers searched for written records of the GAL’s custody or placement recommendations in each case but found documentation in less than half. The lack of documentation made it difficult to determine the most frequent recommendation, though the available information tended to favor joint custody more than expected.

The higher-than-expected percentage of joint custody orders in this sample overall suggests that, at minimum, the existence of domestic abuse in a family does not appear to be a strong factor in deciding custody orders, despite Act 130.

Frequency of Court Decisions on Child Custody

In cases with domestic abuse, researchers expected at least 75 percent of final

orders to result in sole custody. Instead, 50 percent of cases resulted in joint

custody.

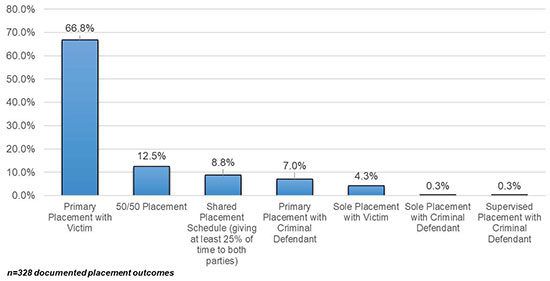

Primary Placement With Domestic Abuse Victim Occurred in Majority of Cases. Based on Act 130’s emphasis on the safety of the child and the nonabusive parent, researchers expected to find high percentages of primary placement with the non-abusive parent. In cases with documented placement outcomes, the most common physical placement order was primary placement with the domestic abuse victim, which occurred in 219 cases (66.8 percent). Unlike custody orders, the data on placement orders came closer to meeting expectations, though it did not reach 75 percent. (See Figure 2, Frequency of Court Decisions on Physical Placement.)

When the abuser was not incarcerated, orders for sole or primary placement with the victim decreased to 61 percent. Of the 239 cases in which the abuser was not in prison, 217 had documented placement orders. Of those cases, the court ordered sole or primary placement to the victim in 133 cases (61 percent). For comparison, according to the U.W. Institute for Research on Poverty, 50 percent of all 2010 placement orders resulting from divorce ended in shared or equal placement.8 Therefore, victims in this sample appear to receive primary or sole placement more often than average. Although this trend is difficult to characterize, it is not dramatic enough to indicate a strong influence from Act 130.

What is more certain is that Act 130 is not widely producing placement orders that explicitly attend to safety. Most final orders in these cases (80 percent) did not include any explicit safety provisions for the victim or children, such as ordering that placement exchange occur in a protected setting. The results show supervised placement is the most common safety provision, but courts only ordered supervised placement in 37 (10.2 percent) cases.

Frequency of Court Decisions on Physical Placement

In cases with domestic abuse, researchers expected to find 75 percent of primary placement with the non-abusive parent. Unlike

custody orders, the data on placement orders came closer to meeting expectations.

Other Findings Reflect Lack of Attention to Domestic Abuse. Other findings also indicate Act 130’s limited influence on this sample. First, only 27.4 percent of all cases include a reference to domestic abuse. In 15 cases, documentation was inaccessible or missing. Therefore, data on the references to domestic violence in those cases is incomplete. While our file reviewers did not have access to sealed documents, nor could they access many transcripts, the lack of written references to domestic abuse appears significant. Institutions, especially courts, “are organized and coordinated, for the most part, by means of standardized texts or standardized protocols for producing texts.”9 If acts of domestic abuse within a family are not routinely noted in family law case files, it suggests that Wisconsin family law case processing does not systematically account for abuse.

Second, even when a GAL or parties’ lawyers are involved, written references to domestic abuse are absent in more than one-half of cases. When the victim had a lawyer or a GAL was appointed, 39 percent and 42 percent of cases referenced domestic violence. Formal domestic abuse findings were much less frequent. Domestic abuse findings were made in only 17 percent (23) of cases with a GAL.10 In over 60 percent of cases in which the victim had representation, the lawyer did not reference domestic violence. These statistics suggest that legal professionals tend to see histories of domestic abuse as irrelevant, unimportant, or unnecessary for courts to make decisions.

The lack of references to domestic abuse also shows that Act 130 exerts little influence on outcomes. The Wisconsin family law system does not appear to systemically attend to the dynamics of domestic abuse when making critical decisions regarding the lives of victims and their children.

If acts of domestic abuse within a family are not routinely noted in family law case files, it suggests that Wisconsin family law case processing does not systematically account for abuse.

Child Exposure to Domestic Abuse Somewhat Ignored in Court Orders. During the pilot test of the survey instrument, data collectors noticed many notations about children witnessing or experiencing abuse. The original research design did not include collecting data on child involvement in the criminal case, but because this study evaluates whether courts account for the best interest of the child, documentation of child exposure to domestic violence helped contextualize these cases. Some degree of child exposure is noted in nearly one-half (165) of cases in this sample. Incidents range from the child’s presence during the violence to physical victimization of the child. Surprisingly, less than one-half of those cases (63) had a GAL.

Exposure to domestic violence affects children’s health and well-being as they grow, and it continues to affect them later in life.11 Therefore, attention to the child’s involvement in, or exposure to, a criminal case between the parents is crucial to determining the best interest of the child. Although courts were marginally more likely to order sole custody and sole or primary placement to the victim in cases with documented child exposure, researchers expected to find a greater difference.

Roundtable Discussion of Study Results

On April 12 and 13, 2018, End Abuse conducted a roundtable discussion with family law practitioners and other individuals to review preliminary study results. Participants from all over Wisconsin, representing many family law disciplines, reviewed the findings. The participants generated a list of barriers and possible solutions. For example, participants discussed barriers to effective GAL practice in domestic abuse cases and recommended steps such as enhanced training, formalized partnerships between GALs and subject matter experts, and heightened GAL practice requirements.

Practitioners also considered ideas such as creating a screening mechanism for domestic abuse in the family law system, differentiated procedural mechanisms for domestic abuse cases, and increased training for judges and lawyers regarding the impact of domestic abuse exposure on children. The roundtable participants also noted the difficulty of accounting for domestic abuse when victims appear in family court and represent themselves and articulated ideas for providing these litigants with resources and tools to better understand and use Act 130 and other legal protections that may apply to their cases. End Abuse will continue to engage with system stakeholders as it explores possible legislative, policy, and Supreme Court Rule changes to adopt some of the proposed solutions.

Acknowledgements

For this study, End Abuse gratefully acknowledges assistance from the Director of State Court’s Office, Office of Court Operations; the State Bar of Wisconsin Family Law Section for financial contributions to bring attendees together for the April roundtable discussion; and the many volunteers and Legal Action of Wisconsin family law attorneys statewide who assisted with data collection.

Meet Our Contributors

What surprised you about your career?

After 23 years at End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin and more than 30 years of working in the domestic abuse movement, I retired in October 2018. What surprised me about my career is that I experienced as many highlights as disappointments in these years.

After 23 years at End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin and more than 30 years of working in the domestic abuse movement, I retired in October 2018. What surprised me about my career is that I experienced as many highlights as disappointments in these years.

Disappointments included encountering legal professionals who refuse to identify the dynamics of domestic abuse or do not know enough about abuse to do so; minimize the abuse or blame the victim; act from the bias that children must be parented equally by both parents; believe the abuse will end when the relationship ends; or believe children are not affected by abuse between the parents.

Highlights include the many legal professionals, legal interns, and law students who work diligently to both understand the complexities of domestic abuse and to address them within the legal system, both in policy and in practice. For all of the latter, I am grateful: victims are more likely to be survivors when the legal system takes their life circumstances seriously.

Teresa (Tess) Meuer, End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, Madison (retired).

What is one of your favorite non-work activities?

One of my favorite non-work activities is taking long bike rides throughout southwest Wisconsin. I usually regret the choice halfway up one of the steep hills in the driftless region. But the second-guessing immediately ends on the way down and especially when sharing a beer with friends after the ride. In the depths of December, I’m counting down the days until spring!

One of my favorite non-work activities is taking long bike rides throughout southwest Wisconsin. I usually regret the choice halfway up one of the steep hills in the driftless region. But the second-guessing immediately ends on the way down and especially when sharing a beer with friends after the ride. In the depths of December, I’m counting down the days until spring!

Tony Gibart, End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, Madison.

What was the most memorable trip you ever took?

The most memorable “trip” I ever took was one semester long. As an undergraduate student, I studied at Harlaxton College in the United Kingdom and lived in a 19th-century manor house. Many factors made it a memorable experience, not least among them the fact that I will probably never live in such a grand house again.

The most memorable “trip” I ever took was one semester long. As an undergraduate student, I studied at Harlaxton College in the United Kingdom and lived in a 19th-century manor house. Many factors made it a memorable experience, not least among them the fact that I will probably never live in such a grand house again.

More importantly, studying abroad introduced me to different cultures and new and diverse perspectives. It deepened my creativity and intellectual curiosity. The experience even inspired my graduate research at Brandeis University. Now, I relish any opportunity I have to travel. Every trip is memorable in its own unique way.

Adrienne Roach, End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, Madison.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 Herbie J. DiFonzo, “From the Rule of One to Shared Parenting: Custody Presumptions in Law and Policy,” Family Court Review 215-16 (April 2014).

2 Wis. Stat. § 767.41(2)(am).

3 Wis. Stat. § 767.41 (2)(d)1.

4 Wis. Stat. § 767.41(5)(bm).

5 Wis. Stat. § 767.41(6)(g).

6 Lauren Wu, “The Interplay Between Domestic Violence Victim Dynamics and Utilization of 2003 Act 130,” Wis. J. Family L. 65-68 (2010).

7 Wis. Stat. § 767.41(5)(bm).

8 Maria Cancian & Daniel R. Meyer, UW-Madison Institute for Research on Poverty, “Child Placement and Child Support” slide 18, (Sept. 25, 2018).

9 Ellen Pence & Dorothy Smith, National Institute of Justice, “Workshops on Violence Against Women/Family Violence” (Oct. 26, 2004).

10 Wis. Stat. § 767.407(4).

11 Governor’s Council on Domestic Abuse & End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, Domestic Abuse Guidebook for Wisconsin Guardians Ad Litem (2017).