March 21, 2013 – Police officers who found cocaine and a gun in defendant Royce Wheeler’s attic obtained the evidence lawfully, a state appeals court has ruled.

Thus, in State v. Wheeler, 2012AP1291-CR (March 19, 2013), a three-judge panel for the District I Appeals Court upheld his convictions for possessing a firearm as a felon and possessing cocaine with intent to deliver, as well as his five-year prison sentence.

In May of 2011, police responded to a domestic disturbance call on Milwaukee’s north side, west of Whitefish Bay. The woman who called said she was assaulted by her baby’s father and she was bleeding. Officers arrived on the scene and began knocking at a common front door that was shared by the upper and lower units of the duplex.

They also knocked on the back doors, the side doors, and the lower-level windows. But nobody answered. After 20 minutes, a woman opened the common door.

The woman, Sasha Bates, told them she lived in the upper unit, and knew nothing about a domestic disturbance. According to police, Bates gave them permission to search the basement. Then, she gave them permission to search the upper unit.

Before they reached the upper unit, two men exited separately. One was Wheeler. All three were detained while police searched the upper unit residence.

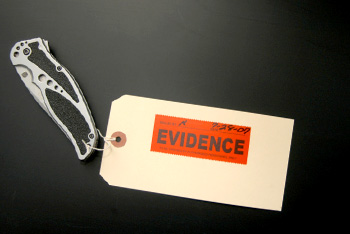

Officers climbed into a small attic through a ceiling panel, and found more than 40 grams of cocaine tucked into a potato chip bag. They also found a gun. Turns out, Wheeler actually lived there, not Bates. So police eventually charged him with the crimes.

He filed a motion to suppress the evidence, but the motion was denied. The trial court ruled that police officers had apparent authority to search because they reasonably believed Bates had authority to consent. The three-judge appeals panel agreed.

The panel rejected Wheeler’s claim that police did not have authority to search. If they did, he argued, they exceeded the scope of Bates’s consent to search.

It noted that the U.S. and Wisconsin constitutions protect individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures, but consent can negate the need to obtain a search warrant. Wheeler argued that Bates did not have the authority to consent to the search.

But the panel also noted that consent is valid, under Illinois v. Rodriguez, 497 U.S. 177 (1990), if police reasonably believe consent was given by someone with authority.

The appeals court rejected Wheeler’s claim that police did not have a reasonable basis to believe Bates had authority to consent because she lied about whether anyone was in the unit. Police should have made more effort to confirm her authority, he argued.

“The presence of other individuals did not necessarily vitiate Bates’s clear assertions – through her words and actions – that she lived in the upper unit,” wrote Judge Joan Kessler. “Moreover, the record demonstrates that Wheeler wanted police to believe that Bates had authority over the upper unit.”

Police testified that after the search and arrest, Bates told them that Wheeler asked her to lie and say the apartment was hers and nobody else was there. Unfortunately for Wheeler, this lie gave police apparent authority to search Wheeler’s apartment.

The panel also rejected Wheeler’s argument that police exceeded the scope of the consent to search by entering the attic and searching the potato chip bag.

“At no point did Bates attempt to limit the scope of the consent by telling officers to avoid the attic space,” Judge Kessler wrote.

As for the cocaine-filled potato chip bag, the plain view doctrine applied. “The bag was already open. By simply obtaining the bag and looking inside, the officers did not violate the scope of their consent,” Judge Kessler explained. This applied to the gun too.

Judge Ralph Adam Fine dissented on this point. He argued that police did exceed their authority when they searched the potato chip bag containing cocaine.

“Of course, only the potato-chip bag was in ‘plain view; the cocaine inside the bag was not,” Judge Fine wrote. “[L]ooking inside the bag was a no-no because the officers were searching for persons, not contraband, and they had no reason to look inside the bag.”