When she retires in July, Justice Shirley Abrahamson will have served 43 years on the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

Photo: Chief Justice Abrahamson, August 2011. Mike De Sisti / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

After 43 years as a justice on the Wisconsin Supreme Court – almost half as chief justice – Shirley Abrahamson is retiring. In July, she ends her fourth, 10-year term on the state’s highest court, capping a career as the longest-serving justice in state history.

“I will miss everything about being here, and I will miss it soon,” Justice Abrahamson said in an interview in late 2018 in her chambers at the State Capitol. “I am not going to run again for a 10-year term at age 85, although I could. And I’d make it, too.”

Abrahamson is a monumental figure in Wisconsin’s judiciary, heading it as chief justice from 1996 to 2015. She was the first woman on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, appointed by Gov. Patrick Lucey in 1976 before her first election in 1979.

The New York native, who made Wisconsin her home, is also revered around the country. Colleagues, including those at the highest levels of the judiciary, understand the important body of work that Justice Abrahamson has contributed to American law.

“Among jurists, Shirley Abrahamson ranks with the very best, the brightest and most caring, the least self-regarding,” said Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. “She never forgets that law exists to serve all the people composing society, not just those in privileged positions.”

“Wisconsin was fortunate to have her steady hand at the helm of its Judiciary,” Justice Ginsburg wrote in a statement. “During her long tenure, she has inspired legions of law graduates to follow in her wake – to pursue justice, equal and accessible to all.”

This article cannot fully capture the deep impact and major accomplishments that Justice Abrahamson achieved in her storied 43-year career as a Wisconsin Supreme Court justice, including 19 years as chief justice. But it attempts to scratch the surface.

Path to Wisconsin

Shirley Schlanger Abrahamson started from humble beginnings. Her parents were first-generation Jewish immigrants from Poland. She was born in the 1930s and grew up in Manhattan. Her father owned a neighborhood store, and the family worked there.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

Joe Forward, Saint Louis Univ. School of Law 2010, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by email or by phone at (608) 250-6161.

Abrahamson, who helped her parents learn English, attended New York City public schools. Her parents, Leo and Celia Schlanger, didn’t know any lawyers. But at age 6, Abrahamson told her parents she wanted to be one.

“I am the child of immigrants, and I think that influenced me a great deal, that this country was open. My mother and father told me I could do anything I put my mind to. No doors were to be closed,” said Abrahamson, who set her mind on the law.

After graduating from New York University in three years, Abrahamson entered law school at the University of Indiana in 1953 at age 19. She was the only woman in her graduating law school class and finished first in the class in 1956.

Abrahamson didn’t view male-dominated law schools or a male-dominated legal profession as challenges, just facts of life in those times. “Coming through college, it was evident there weren’t going to be many women in the field of law,” she said.

At that time, only 3 percent of law school students were women. Her law school dean, who usually placed the top graduate in the largest Indianapolis firm, said the firm would not take a woman. Abrahamson told the dean she wasn’t interested, anyway.

Abrahamson was on her way to Madison, where her husband Seymour had secured a post-doctoral fellowship in zoology. A chance encounter with a dinner party guest,1 in 1956, connected Abrahamson to U.W. Law School Professor J. Willard Hurst.

Hurst, “generally recognized as the father of modern American legal history,”2 was also a former law clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis.3 As Abrahamson has noted, Hurst was an important mentor to her and many others in the legal community.4

In 1962, under Hurst, Abrahamson obtained an S.J.D. in American legal history, the highest law degree the law school confers, and joined the U.W. Law School faculty, where she would continue to teach occasional classes while a justice on the court.

Gordon Sinykin and James E. Doyle of LaFollette & Sinykin also hired Abrahamson as the firm’s first woman attorney. She became a named partner and practiced law for 14 years before Gov. Lucey tapped her for the supreme court, in 1976, at age 42.

First Woman Justice

Being the first woman to serve on the state supreme court does not hold great significance for Justice Abrahamson. While historically significant, Justice Abrahamson saw herself simply as a new justice on the supreme court, not a new woman justice.

Media coverage of her investiture, and the questions posed to her in 1976 and later, mostly centered on her womanhood, her gender status, as if this new woman justice of the supreme court was about to upend decades of male-established precedent.

Abrahamson didn’t see the importance of gender in judging cases that reflect the myriad issues in society, and the diversity of people within it, including both men and women.

As she would later write, “[m]y gender – or, more properly, the experiences that my gender has forced upon me – has, of course, made me sensitive to certain issues, both legal and nonlegal. So have other parts of my background. My point is that nobody is just a man or a woman. Each of us is a person with diverse experiences.”5

In other words, Abrahamson brought a new perspective to the bench. But her perspective was based on much more than her gender. Still, the significance of her appointment and tenure on the court, as a woman, cannot be understated.

Abrahamson was certainly aware of gender discrimination. As a young lawyer, she was excluded from eating lunch at the private, male-only Madison Club, which changed its men-only policy when her clients complained and the newspapers caught wind.

As more women entered the legal profession, they saw Justice Abrahamson among the women lawyers and judges blazing a path to succeed in a male-dominated profession.

Attorney Kathryn Bullon, a member of the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Board of Governors, graduated from the U.W. Law School in 1980, four years after Abrahamson took the bench. As a law student, she took Abrahamson’s seminar on legislative process and policy.

“We saw a woman who came before us, in even less welcoming times, and rose to the state supreme court through her intellect and scholarship, her years in private practice, and her work ethic,” Bullon said. “When we sat down with her, it became absolutely concrete for us women that we can do this. This is a woman who has done it.”

Fellow Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, also Abrahamson’s former student, said Abrahamson often counseled young women. “The number of women who can say they went to law school because of her, I think, is a significant number,” Justice Bradley said.

Four decades later, six of seven justices on the Wisconsin Supreme Court are women. For the first time in the court’s 171-year history, there is only one man, Justice Daniel Kelly.

“For years, they asked me about being the only woman on the court. I don’t think they’ve asked Justice Dan Kelly enough about being the only man,” Abrahamson joked.

Justice Abrahamson in chambers. She became the first woman on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, appointed by Gov. Patrick Lucey in 1976 before her first election in 1979.

Into the Fray

After her appointment, Justice Abrahamson settled into the business of the court. Over the next four decades, Abrahamson became the longest-serving state court judge in Wisconsin history, perhaps the country,6 as she developed her judicial acumen.

In her first term (1976-77), Abrahamson made her presence known, writing 57 opinions, more than any other justice that term, and the most she ever wrote in any term.7 Of them, 40 were majority opinions, 13 were dissents, and four were concurrences.

“I remember my first day in conference,” she said. “Each justice would summarize one of the cases. My turn came, my first appearance internally, and I said ‘my client says. …’ Of course, I didn’t have a client, I’m no longer an advocate. I have a new way of thinking here. It was a sharp awakening to me, and everyone was vastly amused.”

Abrahamson’s first writing was a unanimous opinion. More notable were her first dissents, which showed early confidence to break stride with the majority. In her first term, she was the lone dissenter in 9 of 10 decisions decided 6-1 (or 5-1).8

In one of those cases, Abrahamson would have granted worker’s compensation death benefits to the posthumous child of a man who died from work injuries.9 In another, she would have upheld an arbitration award granting a discharged city employee reinstatement and back pay.10

Over four decades, Justice Abrahamson would go on to write more than 1,300 opinions. The trajectory of her writings, in terms of majority and dissenting opinions, tells a story about her evolving jurisprudence, as well as the shifting balance of the court over time.

U.S. District Court Judge Barbara Crabb and Justice Shirley Abrahamson were featured participants at the 2018 Robert W. Kastenmeier Lecture at the U.W. Law School. Photo: Mike Hall

Judicial Philosophy

The early dissents provided a glimpse of Abrahamson’s approach to certain issues, including Fourth Amendment search and seizure cases, which often come before the supreme court to examine whether police conduct crosses the constitutional line.

In the first dissent of her career, Justice Abrahamson would have ruled that police officers were not legally justified in searching an African-American man – later convicted of carrying a concealed weapon and armed robbery, party to the crime – because police did not have “reasonable suspicion” to believe the defendant committed a crime.11

In later Fourth Amendment cases, Abrahamson continued to rail against intrusions on individual rights. Recently, she said police could not use an exception to justify a warrantless request for cell phone tracking data on a murder suspect.12

“The lead opinion’s exigent circumstances exception swallows the rule of the warrant requirement,” wrote then-Chief Justice Abrahamson, the sole dissenter. “I decline to undercut the warrant requirement or ignore the heavy burden placed on the State to prove the exigent circumstances exception to the warrant requirement.”13

Asked about her judicial philosophy, Abrahamson had a simple response: “My judicial philosophy is to examine the facts, the law, and the precedent. You apply the facts to the law and the precedent as you understand them, and you reach a decision.”

On the question of how justices can reach different conclusions, how some of the same justices often disagree with other justices, on similar cases, Abrahamson provided a simple analogy and described how other justices might reach different conclusions.

“It’s important that we apply the same rule of law to everybody, because that is only fair and you learn that as a child,” she said. “If your brother gets one cookie, there has to be a really good reason you don’t have one cookie, because that’s equal protection.”

“The second part is that you apply the same rule to the same circumstance. You don’t apply the same cookie rule to a 10 year old as you do a 3 month old, who can’t swallow cookies. When you apply the same circumstance, you apply the same law.”

Justice Abrahamson said judges reach different conclusions because the law is used in general terms, but they apply the law to specific facts and circumstances in every case.

“When there are different circumstances, you can get different applications, but the law is the same. We are talking about who is entitled to cookies and how many,” she said.

Midnight Oil

Shirley Abrahamson is well known for her work ethic. In the early years, she and her husband Seymour raised their son Daniel, now a lecturer at the University of Virginia Law School. As a young justice, and throughout her career, she burned the midnight oil.

“You figure the time you’ve got and you sort it out so that everybody has a fair share of your time. You make it count,” said Justice Abrahamson.

Justice Ann Walsh Bradley says Abrahamson was a fixture the Wisconsin State Capitol’s night custodians had to work around. “One of the things I remember is the close relationship she had with the night custodians. They uniformly liked her.

“When I got on the court, we both worked late hours, sometimes until midnight or 1 a.m. The difference is, Shirley did it every night.”

As Bradley recalled, after Abrahamson won her 1999 reelection, someone had to swear her in. “You have to make sure a justice is sworn in before the term starts in August. It was near the end of the term, and we would be taking different paths.

“I swore her in around midnight, just the two of us and the cleaning lady, a dear friend of ours, who took a picture. But you asked about her work ethic, and I’ll tell you this.

“Janine Geske, a former justice, described Shirley Abrahamson as the hardest working, smartest person she has ever met, and I think that is accurate,” Bradley said.

Rising Up

The people of Wisconsin approved of Abrahamson in 1979, when she won her first election to a 10-year term. The people elected her to another 10-year term in 1989. Then, 20 years into her judicial career, at age 62, she became the most senior justice.

Under the Wisconsin Constitution, at the time, the most senior justice was appointed chief justice. Abrahamson became chief justice in 1996. William Rehnquist, a Wisconsin native and then Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, swore her into office.

The people of Wisconsin supported Chief Justice Abrahamson again in 1999, electing her to a third, 10-year term. By the time Justice Abrahamson became chief justice, she was already well known in judicial circles at the highest levels, both state and federal.

In 1979, the year she won her first election, she was on Democratic President Jimmy Carter’s short-list to replace U.S. Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan Jr., who was rumored to be contemplating retirement.14 Justice Brennan did not retire until 1990.

In 1993, before Abrahamson became chief, she appeared on Democratic President Bill Clinton’s short-list of candidates to replace U.S. Supreme Court Justice Byron White.15

President Clinton ultimately picked Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Like Abrahamson, Ginsburg grew up in New York City, and has remained a powerful voice on the High Court’s so-called liberal bloc ever since.

Abrahamson, of course, is considered a “liberal” justice, a term used frequently to describe judges whose rulings favor liberal causes, or oppose “conservative” ones.

The labels often appear when judges or justices have ruled in politically charged cases. As the legal community understands, the nuances of “liberal” and “conservative” jurisprudence are often misconstrued and overgeneralized by politicians and the media.

Abrahamson does not subscribe to or pay attention to the political labeling of justices, who are independent decision-makers and serve as a check on legislative and executive power. “Somebody has decided on what the issue is and the consistency between justices, so they have imposed that on the court,” she said. “I don’t. I write.”

One of the areas in which Chief Justice Abrahamson focused her thinking and scholarly work was state constitutionalism, or “new federalism,” the idea that the federal Constitution provides “minimum” guarantees of individual rights, but judges can look to state law, and state constitutions, as providing more layers of protection.

In the 1990s, Abrahamson became one of the country’s preeminent judicial scholars in this area. As fellow Justice Ann Walsh Bradley noted in a 2004 issue of the Albany Law Review, the entirety of which was dedicated to Chief Justice Abrahamson:

“Her legal scholarship has brought her international acclaim, leadership positions in national organizations, fourteen honorary doctor of law degrees, and lecture requests from around the world.”16

Even respected jurists who disagreed with new federalism, and Abrahamson’s judicial philosophy, respect her intellect. “Justice Abrahamson is a brilliant legal thinker, a powerful writer, and trailblazer in the law,” said Judge Diane Sykes of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Sykes served on the Wisconsin Supreme Court from 1999 to 2004.

“She’s been a champion of equal justice, individual rights, and an independent judiciary,” Judge Sykes continued. “We have different views on legal interpretation and the role of the courts, but her work always made mine better. She has made an outsized and lasting mark on our state law.”17

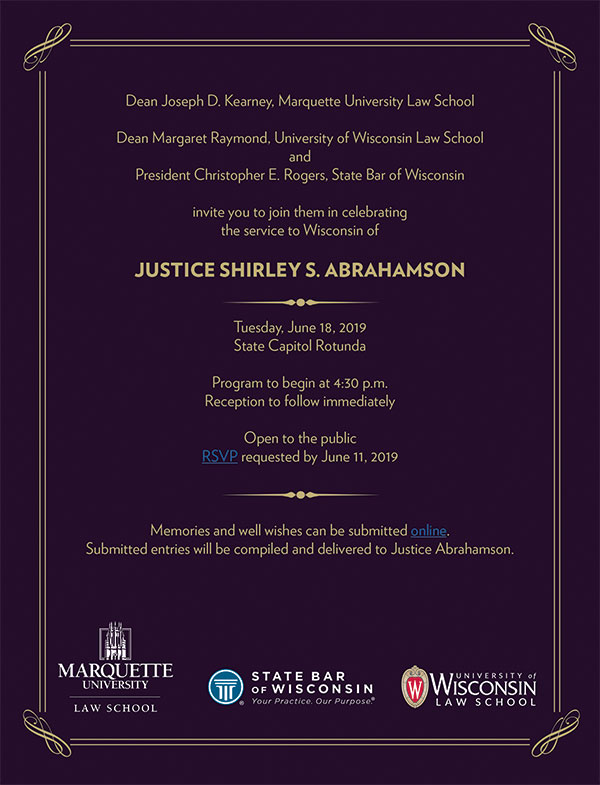

Join us in celebrating Justice Abrahamson: Tuesday, June 18, at the State Capitol. RSVP now.

Heading the Judicial System

Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, who was elected to the court in 1995 and will become the senior justice upon Abrahamson’s departure, said Abrahamson’s judicial acumen is rivaled only by her leadership skills, which have “shaped the contours of Wisconsin’s approach to the administration of justice.”18

Under the state constitution, Wisconsin’s chief justice “shall be the administrative head of the judicial system and shall exercise this administrative authority pursuant to procedures adopted by the Supreme Court.” The chief is the court’s top administrator.

“Shirley was, just as much in terms of the law itself, the top state supreme court justice in the nation, and I mean top, number one, when it came to being on the cutting edge administratively,” Justice Bradley said in a recent interview.

In addition to presiding at the court’s meetings, including oral arguments and conferences, then Chief Justice Abrahamson was instrumental in starting court-related volunteer programs that give the public more access to the court system.

From teen courts to conflict resolution centers, from domestic abuse services to legal assistance clinics, then Chief Justice Abrahamson tapped a “shoestring budget” to expand, support, and help create new programs in counties statewide. A fourth edition catalogof those programs, published in 2013, identified nearly 150 programs in operation.

“Wisconsin is a leader on these programs,” Bradley said. “It’s because Shirley had a national reputation with national contacts to help these programs get off the ground.

“Administration, besides a brilliant legal mind in terms of the law, has really marked her tenure on the court,” said Justice Bradley, noting that Justice Abrahamson’s unique brand of wit and humor help her connect with people from all walks of life.

Abrahamson also started the Court with Class program, which brings in high school students statewide to witness the supreme court’s oral arguments and learn more about the justice system in action. Thousands of students have participated.

Other chief justices around the nation recognized Abrahamson’s talents. She was elected president of the Conference of Chief Justices (2004-05), which brings the chief justices together to “meet and discuss matters of importance in improving the administration of justice” and the organization and operation of state courts.

Former Alaska Supreme Court Chief Justice Dana Fabe, first appointed in 1996, was the first woman to serve on that court and served three terms as chief justice.19 She first met Abrahamson at the Conference of Chief Justices, in her first term.

“She really tucked me under her wing,” said Justice Fabe in an interview. “She was so inclusive, and introduced me to the other chief justices. She was instrumental in helping me develop as a chief justice, and she was always available to provide guidance.”

Ronald George, the former chief justice of the California Supreme Court, called Abrahamson a “technologically astute” and “forward thinking jurist” who brought her scholarly perspective to various national committees throughout the years.

“I am sure that we have seen only a glimpse of what will become Shirley Abrahamson’s enduring legacy,” George wrote in 2004.20

The Sun Must Set

Justice Abrahamson’s final, 10-year term has not been easy. A politically polarized Wisconsin put the state supreme court center stage on many politically charged cases, with Chief Justice Abrahamson often the target of divisive rhetoric that cut both ways. Some blamed Abrahamson as a major contributor to the court’s own divisiveness.

In 2015, the people of Wisconsin passed a constitutional amendment, allowing the justices themselves to select the chief justice and eliminating the seniority rule. Justice Patience Roggensack replaced Abrahamson as the new chief justice in April 2015.

Abrahamson, known for her work ethic, did not relent, although much of her work product is revealed in dissents and concurrences, which is not unusual. In the 2013-14 term for instance, she wrote 27 dissents, the most dissents of any term.21

“Dissents are important on several levels, and you just don’t dissent to dissent. It takes a lot of effort,” Justice Abrahamson said. “You do it because you think it’s a good process for the bench and bar to follow what the disagreement is about.”

Not including the court’s current term, Abrahamson has written 530 majority opinions, 490 dissents, and 325 concurring opinions.22 Those numbers will increase when her final opinions are published in the coming months. In addition, a cursory search notes she has written nearly 40 law review articles in her career.

Justice Ann Walsh Bradley said Abrahamson’s body of work shows a commitment to individual rights, transparency and government accountability, and cutting-edge administrative leadership that moved Wisconsin’s court system to the forefront.

“She has also been one of the most prolific writers of all state court justices with a profound effect on the development of law, not only in Wisconsin,” Bradley said.

In 2016, Abrahamson’s husband of more than 60 years passed away. Last year, she publicly announced a cancer diagnosis, and announced that she would retire when her term expires on July 31, 2019, after completing her fourth consecutive, 10-year term.

Abrahamson will retire with an extensive portfolio and few regrets. “I’m sure I could have done things smarter. I’m sure I made mistakes along the way,” Abrahamson said. “But I can’t think of anything major that I would do differently in my career.”

“I would hope I could do things better if I had to do them a second time, but I think I’ve lived my life well and I tried my best. I’m not looking to redo it. Once is enough.”

Former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Janine Geske (1993-98) said Abrahamson’s “positive impact on the law within our state, nationally and internationally is impressive and unparalleled. As chief justice, she left a legacy of excellent scholarship and leadership in collaboratively advancing the Wisconsin judiciary into a national model of justice and innovation, a perfect example of public servant leadership,” Geske said.

Justice Rebecca Dallet, the newest member of the court, holds Justice Abrahamson in the highest regard. “She will leave behind a legacy of incredible legal acumen and thoughtfulness, a commitment to the law and making sure everyone’s rights have been protected,” Dallet said. “I hope to follow in those footsteps, if that’s even possible.”

Authored Opinions by Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson

| Term |

Majority

Opinions |

Dissenting

Opinions |

Concurring

Opinions |

Total

Opinions |

1976-77 |

40 |

13 |

4 |

57 |

1977-78 |

32 |

9 |

7 |

48 |

1978-79 |

33 |

1 |

2 |

36 |

1979-80 |

26 |

19 |

3 |

48 |

1980-81 |

18 |

15 |

11 |

44 |

1981-82 |

17 |

16 |

3 |

36 |

1982-83 |

21 |

14 |

10 |

45 |

1983-84 |

16 |

19 |

16 |

51 |

1984-85 |

12 |

10 |

7 |

29 |

1985-86 |

8 |

9 |

6 |

23 |

1986-87 |

12 |

13 |

10 |

35 |

1987-88 |

10 |

2 |

3 |

15 |

1988-89 |

12 |

5 |

4 |

21 |

1989-90 |

9 |

11 |

5 |

25 |

1990-91 |

11 |

16 |

7 |

34 |

1991-92 |

9 |

8 |

6 |

23 |

1992-93 |

12 |

16 |

2 |

30 |

1993-94 |

11 |

11 |

7 |

29 |

1994-95 |

9 |

9 |

6 |

24 |

1995-96 |

11 |

7 |

9 |

27 |

1996-97* |

12 |

4 |

12 |

28 |

1997-98 |

10 |

8 |

6 |

24 |

1998-99 |

12 |

8 |

4 |

24 |

1999-00 |

10 |

13 |

8 |

31 |

2000-01 |

12 |

14 |

17 |

43 |

2001-02 |

11 |

15 |

6 |

32 |

2002-03 |

12 |

17 |

17 |

46 |

2003-04 |

12 |

16 |

10 |

38 |

2004-05 |

13 |

10 |

8 |

31 |

2005-06 |

11 |

10 |

11 |

32 |

2006-07 |

9 |

13 |

8 |

30 |

2007-08 |

9 |

3 |

13 |

25 |

2008-09 |

9 |

3 |

6 |

18 |

2009-10 |

8 |

12 |

10 |

30 |

2010-11 |

7 |

18 |

4 |

29 |

2011-12 |

8 |

13 |

9 |

30 |

2012-13 |

5 |

8 |

10 |

23 |

2013-14 |

7 |

27 |

6 |

40 |

2014-15 |

7 |

13 |

10 |

30 |

2015-16** |

5 |

14 |

5 |

24 |

2016-17 |

5 |

15 |

9 |

29 |

2017-18 |

7 |

13 |

5 |

25 |

2018-19 |

N/C |

N/C |

N/C |

N/C |

Total |

530 |

490 |

325 |

1,345 |

Source: SCOWstats

*Begins service as Chief Justice

** Ends service as Chief Justice

Endnotes

1 Shirley Abrahamson, Eulogy for James Willard Hurst, 1997 Wis. L. Rev. 1125 (1997).

2 U.W. Law School, More on J. Willard Hurst.

3 Abrahamson, supra note 1.

4 Id.

5 Shirley Abrahamson, “The Woman Has Robes: Four Questions,” Pioneers in the Law: The First 150 Women, State Bar of Wisconsin (1998).

6 It has been reported that Justice Abrahamson is the longest-serving state justice in the country.

7 SCOWstats, Statistics for Individual Years (1976-2018) (author compiled).

8 SCOWstats, Statistics for Individual Years (1976-77).

9 Larson v. Wisconsin Dep't of Indus., Labor & Human Relations, 76 Wis. 2d 595, 252 N.W.2d 33 (1977).

10 Wisconsin Employment Relations Comm'n v. Teamsters Local No. 563, 75 Wis. 2d 602, 250 N.W.2d 696 (1977), overruled by City of Madison v. Madison Prof'l Police Officers Ass'n, 144 Wis. 2d 576, 425 N.W.2d 8 (1988).

11 Penister v. State, 74 Wis. 2d 94, 105, 246 N.W.2d 115 (1976).

12 State v. Subdiaz-Osorio, 2014 WI 87, ¶ 207, 357 Wis. 2d 41, 849 N.W.2d 748. See also Joe Forward, Deeply Divided Court Rules in Warrantless Cell Phone Tracking Case, State Bar of Wisconsin, WisBar News (Aug. 29, 2014).

13 Id.

14 Choice of Woman on High Court Seen, New York Times (Nov. 25, 1979).

15 Stephen Labaton, Shifting List of Prospects to be Justice, New York Times (May 9, 1993).

16 Hon. Ann Walsh Bradley, With Courage and Passion: The Inspired Leadership of Chief Justice Shirley S. Abrahamson, 67 Alb. L. Rev. 641, 641 (2004).

17 Hon. Diane S. Sykes, The "New Federalism": Confessions of A Former State Supreme Court Justice, 38 Okla. City U. L. Rev. 367, 379 (2013).

18 Bradley, supra note 16.

19 In Alaska, the chief justice holds office for three years and cannot serve consecutive terms.

20 Hon. Ronald M. George, A Dedication to Shirley S. Abrahamson, 67 Alb. L. Rev. 641, 647 (2004).

21 SCOWstats, Statistics for Individual Years (2013-14).

22 SCOWstats, Statistics for Individual Years (1976-2018) (author compiled).