May 10, 2024 – A landlord violated the Wisconsin Consumers Act by serving an eviction notice on a tenant during a 60-day moratorium on evictions for failure to pay rent, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals (District III) has held in Koble Investments v. Marquardt, 2022AP182 (April 23, 2024).

In May 2019, Elicia Marquardt signed a 12-month apartment lease with Koble Investments (Koble).

On March 27, 2020, Gov. Tony Evers issued a 60-day emergency order that prohibited landlords from serving eviction notices for failing to pay rent.

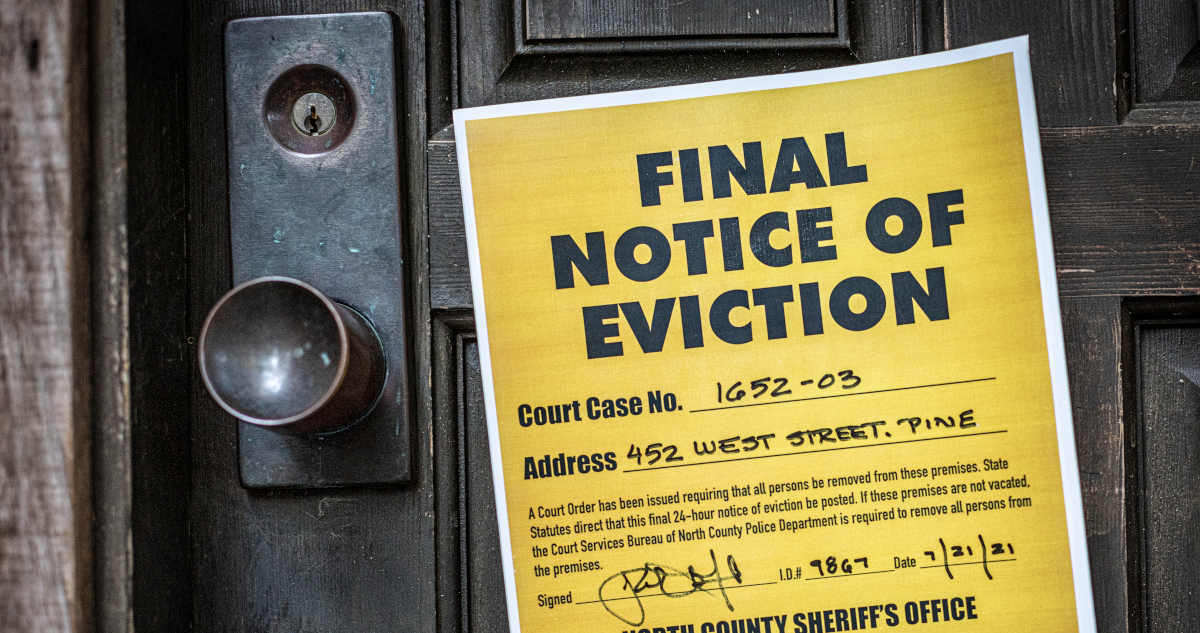

During the 60-day period, on May 15, Koble delivered to Marquardt a five-day eviction notice, for failure to pay rent.

On June 2, Koble filed an eviction action against Marquardt in Marathon County Circuit Court. In addition to seeking to evict Marquardt, Koble sought $1,548 in damages.

Answer and Counterclaims

Marquardt filed an answer and counterclaims.

Marquardt asserted that the lease was void and unenforceable under Wis. Stat. section 704.44(10) and Wis. Admin. Code section ATCP 134.08(10).

Jeff M. Brown , Willamette Univ. School of Law 1997, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by

email or by phone at (608) 250-6126.

Jeff M. Brown , Willamette Univ. School of Law 1997, is a legal writer for the State Bar of Wisconsin, Madison. He can be reached by

email or by phone at (608) 250-6126.

She also asserted that Koble had violated the Wisconsin Consumers Act (WCA) by serving the five-day eviction notice during the 60-day period specified by the governor’s order.

Upon Koble’s motion, a court commissioner dismissed the company’s eviction claim. Koble filed an answer to Marquardt’s counterclaims. The company admitted filing the eviction notice during the 60-day period.

Marquardt then filed a claim for attorney fees. James Miller, Marquardt’s attorney, moved to intervene.

Appeal to Circuit Court

The court commissioner dismissed Marquardt’s counterclaims, denied her claim for attorney fees, and denied Miller’s motion.

Marquardt appealed for a trial de novo before the circuit court.

The circuit court ruled that Koble hadn’t violated section 704.44(10) or section ATCP 134.08(10) and denied Miller’s motion to intervene; it also denied Miller’s motion for attorney fees.

The circuit court later denied Marquardt’s remaining counterclaim but allowed Miller to intervene in Marquardt’s counterclaims so he could appeal.

Lease Covered by WCA

On appeal, Koble argued that Marquardt’s lease wasn’t covered by the WCA.

Miller argued that executing the lease was a “consumer transaction” as defined in section 421.301(13) of the WCA.

That section defines “consumer transaction” as “a transaction in which one or more of the parties is a customer for purposes of that transaction.”

Writing for a three-judge panel, Presiding Judge Lisa Stark concluded that the lease was a “consumer transaction” under the WCA because section 421.301(17) defines “customer” as “a person other than an organization … who seeks or acquires real or personal property, services, money or credit for personal, family or household purposes.”

“The undisputed facts of this case establish that Marquardt was a ‘customer’ under the definition of section 421.301(17) because she acquired real property for personal, family, or household purposes,” Stark wrote.

“Specifically, she acquired a leasehold interest in a residential apartment for personal use.”

Judge Stark also pointed out that under section 423.201(1), a “[c]onsumer approval transaction’ means ‘a consumer transaction other than a sale or lease … of real property.’”

“If the term ‘consumer transaction’ did not include a lease of real property, there would be no need for section 423.201(1) to state that the term ‘[c]onsumer approval transaction’ means a consumer transaction ‘other than a … lease … of real property,’” Stark wrote.

Koble Was Debt Collector

Judge Stark also concluded that the lease was a consumer transaction that included “an agreement defer payment” under section 427.104(1) of the WCA, because Marquardt was not required to pay the full amount of the 12 months’ rent up front.

Koble argued that section 427.104(1) didn’t apply to the lease and cited three Wisconsin Supreme Court cases involving deferred credit payments.

But Stark pointed out that section 427.104(1) applied to attempts “to collect an alleged debt arising from a consumer credit transaction or other consumer transaction … where there is an agreement to defer payment.”

“Koble’s proposed interpretation of section 427.104(1) would essentially render the words ‘or other consumer transaction’ surplusage,” Judge Stark wrote.

Because section 427.104(1) applied to the lease, Stark concluded that Koble was acting as a debt collector when it served the five-day eviction notice on Marquardt, and was subject to section 427.104(1)(j), which prohibits a debt collector from “[C]laim[ing], attempt[ing] or threaten[ing] to enforce a right with knowledge or reason to know that the right does not exist.”

Koble violated section 427.104(1)(j) by serving the eviction notice during the 60-day period in which the governor’s order was in effect, Judge Stark concluded.

“Having reviewed the governor’s unambiguous emergency order, Koble should have understood – or, stated differently, had reason to know – that it could not serve a five-day eviction notice for failure to pay rent during the moratorium period,” Stark wrote.

Judge Stark concluded that Miller was entitled to his attorney fees, because Koble had violated section 427.104(1)(j) and Koble had dismissed its eviction action against Marquardt.

Lease Lacked Notice

Stark also concluded that the lease was void and unenforceable because it allowed Koble to terminate the lease for a crime committed in relation to the property but didn’t include the notice of domestic abuse protections mandated by section 704.14 and Wis. Admin. Code section ATCP 134.08(10).

Those sections require wording that provides that a tenant has a defense to a landlord’s right to terminate a lease for criminal activity if: 1) the tenant proves the landlord knew or should have known that he or she was a victim of domestic assault; and 2) the tenant had either sought an injunction against the person behind the criminal activity or told the landlord in writing that the person was no longer a guest of the tenant’s.

Stark pointed out that under section 100.20(5), anyone who loses money because of a violation of Wis. Admin. Code ch. ATCP 134 is entitled to twice the amount of that loss, plus costs and attorney fees, and concluded that Marquard was entitled to her costs, attorney fees, and twice her losses.

The Court of Appeals reversed the circuit court and remanded the case.