In March 1856, Abraham Lincoln waded into a bitter legal dispute over land rights in Beloit, Wis. The case brought him into direct conflict with one of Wisconsin’s great early lawyers, Matthew Hale Carpenter, who would go on to argue 97 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court.1

Lincoln was hired by Beloit landowners to provide a legal analysis refuting Carpenter’s contention that because land ownership had been conveyed to the residents before government land patents were issued, the land ownership was invalid.2

Carpenter, himself a Beloit resident at the time, contended that his father-in-law, Paul Dillingham, who had been conveyed similar title after the land patents were obtained, was the lawful owner of vast swaths of land in Beloit.

Carpenter and Beloit in 1848

Carpenter’s storied legal career in Wisconsin began when he came to Beloit in 1848 from Vermont as a 23-year-old newly minted lawyer. Beloit at the time was a thriving but very rudimentary small town. There were about 1,700 residents but no water system, no garbage collection, and no remedial plumbing.3

Beloit, however, was on the receiving end of a growing migration from the northeastern part of the United States. Spurred by efforts of the Beloit “New England Emigrating Society,” the population of Beloit would double and then triple in only a few years.4 Land became coveted.

The charismatic Carpenter arrived by horse-drawn coach, hung up a shingle advertising a law practice, and took the town and then the state by storm. He soon had a thriving law practice and would later become a U.S. senator and possible presidential candidate.5

But in 1855, Carpenter took on a case that seemed to go against his ambitious nature. Attempting to exploit a technicality that most Beloit landowners had been conveyed their property before the government had granted land patents, Carpenter arranged for his father-in-law, Dillingham, to be conveyed similar title from the original owner. Carpenter then publicly claimed that Dillingham was the rightful owner of most of the land in Beloit.

The Legal Dispute

In the 1830s, the federal government passed a series of laws authorizing the sale of government land in the then “western” United States, now the Midwest. Similar to the later Homestead Act, the laws, called “Preemption Acts,” gave a right of first refusal for purchase to anyone who had initially settled or cultivated the land, with the government’s price usually below what the prevailing market would bear. If the preemption right was exercised, the government would issue a land patent declaring the land ownership to be in the name of the settler.

The original act, in 1830, specified that the right of preemption would last for only one year and, to discourage speculation, voided any prior transfer of the right to preemption before a land patent was issued. In 1832, Congress renewed the 1830 law but added that the right of preemption could be legally transferred before the land patent was issued. Additional laws in 1834 and 1838 also extended the initial 1830 preemption right but made no mention of whether the 1832 provision allowing transfer was still valid.

Robert P. Crane held the right of preemption for much of the land comprising Beloit. In 1838, he sold the land to a large group of Beloit residents, but the land patents in Crane’s name were not issued by the federal government until 1842.

Carpenter, seizing upon the original wording of the 1830 act voiding transfers before the issuance of the land patents, convinced Crane to sell the same property a second time – ultimately to Carpenter’s father-in-law, Dillingham. Carpenter then publicly declared that his father-in-law was the true legal owner of much of the property in Beloit.

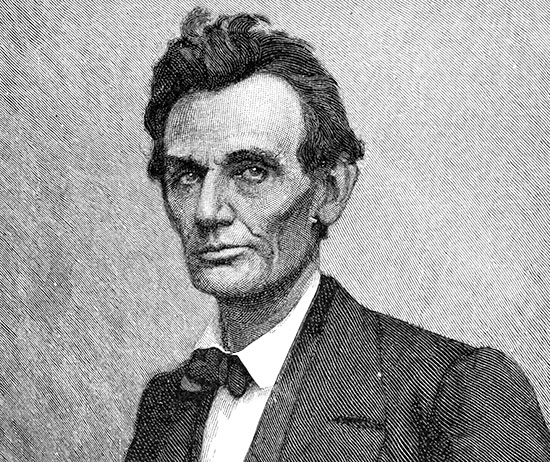

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln, 1860 - stock illustration.

Lincoln to the Rescue

Historians describe the ensuing legal dispute as chaotic, with Carpenter at one point almost being lynched by his angry neighbors. Carpenter, however, refused to be intimidated. He claimed his motive was not to steal his neighbors’ land but to punish land speculators. Carpenter said he would sell the land back to his neighbors at a “nominal” price.6

One aggrieved Beloit resident, Lucas Fisher, sought help from an Illinois connection, a judge named David Davis. Davis recommended Lincoln. According to Illinois historian Tom Emery, Lincoln was paid $100 to provide a legal analysis for Fisher and others.7

Lincoln’s written legal work on the issue is titled Opinion on Land Titles in Beloit, Wisconsin, March 24, 1856 and is available online through the University of Michigan.8

In a dry analysis of the available law, Lincoln argued that the Beloit residents, not Dillingham, properly held title under both law and equity. Lincoln first set forth that Crane’s initial transfer of his property interest in the land was valid on its face because it otherwise complied with all laws providing for the transfer of land ownership. The legal interest was described with particularity and had been transferred by deed, duly recorded.

Lincoln then turned to the effect of the Preemption Acts. The issue was whether the original pre-patent transfer prohibition of the 1830 act or the permissible transfer of the 1832 act applied when Congress later renewed preemption without clarifying the issue.

Lincoln pointed out that U.S. Attorney General Benjamin Butler had issued an opinion in 1835 determining that the 1834 renewal encompassed the 1832 version, not the original 1830 prohibition on transfer. Lincoln further noted that thereafter, Congress, well aware of Butler’s conclusion, renewed preemption again in 1838 without taking issue with Butler’s construction.

According to Lincoln, there also was an Illinois federal case directly on point. In Morgan v. Curtenius,9 the district court held that a transfer of land ownership in 1838 before the issuance of a land patent was still valid under the Preemption Act of 1834. “This is our case precisely,” Lincoln wrote.

As an additional point, Lincoln said that his clients had the stronger case in equity because Carpenter’s father-in-law had full knowledge of the prior deeds when acquiring his own.

Lincoln then added the following recommendation:

“I should advise [our clients] to pay nothing [to clear title]; to bring no suit of their own, but quietly await the attack of the adversary. If the attack shall ever be made, it will be made at law, and certainly should be defended at law; and if, finally, the interposition of a court of Equity shall become necessary, there will still be time and oppertunity [sic] of resorting to it. A. LINCOLN. March 24, 1856.”

In fact, a legal challenge did follow, and the case eventually made its way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Although other lawyers argued on behalf of Fisher, they used Lincoln’s arguments to prevail. The Wisconsin court even favorably cited the Illinois case, Morgan, that Lincoln had referenced. A year later, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a separate case out of Louisiana, settled the matter for good by confirming that the 1830 prohibition did not apply to any preemption rights transferred after 1832.10

Historian Thompson said that Lincoln’s work brought a collective sigh of relief to the Beloit residents, and Lincoln was roundly credited with saving their land.11 Four years later, Lincoln would easily carry Beloit during the 1860 presidential election, winning 557 votes of about 800 cast.12

Carpenter, on the other hand, decided the time was right to move to Milwaukee and open a law office there. In Milwaukee, Carpenter thrived as a railroad-litigation lawyer (representing investors who sued railroads) and as an advocate before the U.S. Supreme Court, eventually attracting a national clientele.

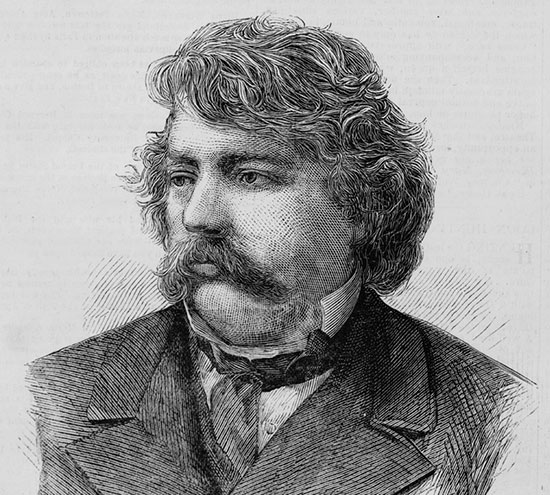

Matthew Hale Carpenter, U.S. Senator, 1874. Portrait illustration in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper by F. Thorp, artist, 1874 Feb. 21, p. 396. Source: Library of Congress.

Opponents, then Allies

In the years after the Beloit dispute, Carpenter, a staunch Democrat and admirer of Stephen A. Douglas, initially had little admiration for Lincoln’s work as a lawyer or politician. Carpenter called Lincoln “idiotic” and a “damned fool.”13

But Carpenter also was vehemently pro-Union and abhorred the secession of Southern states leading to the Civil War. In 1864, Carpenter led a group of prominent Milwaukee Democrats to publicly support Lincoln. Carpenter, by then also one of Wisconsin’s leading orators, toured the state, giving multiple speeches (sometimes three in one day) urging Lincoln’s reelection. Joining Carpenter on the stump was Judge Arthur MacArthur, a grandfather of World War II general Douglas MacArthur. In the 1864 presidential election in Wisconsin, Lincoln handily defeated General George McClellan by 12 percentage points.14

Carpenter’s support drew the attention and admiration of members of Lincoln’s administration, particularly Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton twice hired Carpenter to argue major cases before the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of the federal government: one when Georgia tried to sue General Ulysses S. Grant for damages caused during the Civil War and another when a Mississippi resident claimed a right to habeas corpus relief even while Mississippi was still in a state of rebellion. Carpenter won both cases, becoming nationally famous in the process.15

After Lincoln was assassinated, Carpenter switched parties and became a Republican. In 1868, he was elected as a U.S. senator from Wisconsin. He initially was very popular among his colleagues and was elected president pro tempore of the Senate, third in line of succession to the presidency. Those in Washington even bandied about his name as a possible presidential candidate for 1876.16

But the same trait that caused Carpenter to sue fellow Beloit residents soon emerged in the Senate, where Carpenter continually picked inopportune fights with fellow Republicans. At other times, Carpenter’s earlier criticism of Lincoln came back to haunt him, especially Carpenter’s comment that Lincoln was an idiot. Carpenter’s personal life also became scandalous when, while his wife was in Wisconsin, national newspapers reported (in the euphemistic words of the day) that Carpenter had been found to be traveling with “too much baggage for a single man.”17 With Republican support waning, Carpenter was defeated in his 1874 bid for reelection. But he later regained a Senate seat in 1878.

Carpenter died of lung congestion in 1881 in the middle of his second Senate term. His death was national news and a memorial for him was held at the U.S. Supreme Court. Arthur MacArthur gave a speech at the high court, tracing Carpenter’s career and referencing his time in Beloit, though MacArthur politely made no mention of the high-stakes legal battle that Carpenter had lost to Lincoln 25 years earlier.18

» Cite this article: 94 Wis. Law. 30-34 (April 2021).

Meet Our Contributors

What is the most important advice you can give a new lawyer?

What is the most important advice you can give a new lawyer?

The same advice my father, Vince (also a lawyer), gave to me: Try to be a good listener. It’s harder for lawyers than you think!

Steven M. Biskupic, Biskupic & Jacobs, Mequon.

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email klester@wisbar.org. Check out our writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 E. Bruce Thompson, Matthew Hale Carpenter: Webster of the West 60 (State Historical Society of Wis., Madison 1954).

2 Id. at 37-48.

3 Id. at 23-25; Robert C. Nesbit, The History of Wisconsin, Volume III, Urbanization and Industrialization 1873-1893, at 484 (State Historical Society of Wis., Madison 1985).

4 Thompson, supra note 1, at 23-25.

5 Id. at 23-25, 216.

6 Id. at 39.

7 Tom Emery, Abraham Lincoln Helped Save Beloit, Wis. State J. (Sept. 6, 2020).

8 https://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln2/1:361?rgn=div1;view=fulltext.

9 4 McLean 336 (1848).

10 Dillingham v. Fisher, 5 Wis. 475 (1856); Marks v. Dickson, 61 U.S. 501 (1857).

11 Thompson, supra note 1, at 39.

12 Weekly Gazette and Free Press 4 (Nov. 9, 1860).

13 Thompson, supra note 1, at 80-81.

14 Id. at 81-83.

15 Georgia v. Grant, 73 U.S. 241 (1867); Ex Parte McCardle, 74 U.S. 506 (1868).

16 Thompson, supra note 1, at 216.

17 Thompson, supra note 1, at 199; Santa Fe New Mexican 1 (Sept. 2, 1873).

18 Memorial Addresses on the Life and Character of Matthew H. Carpenter 96-101 (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1882).