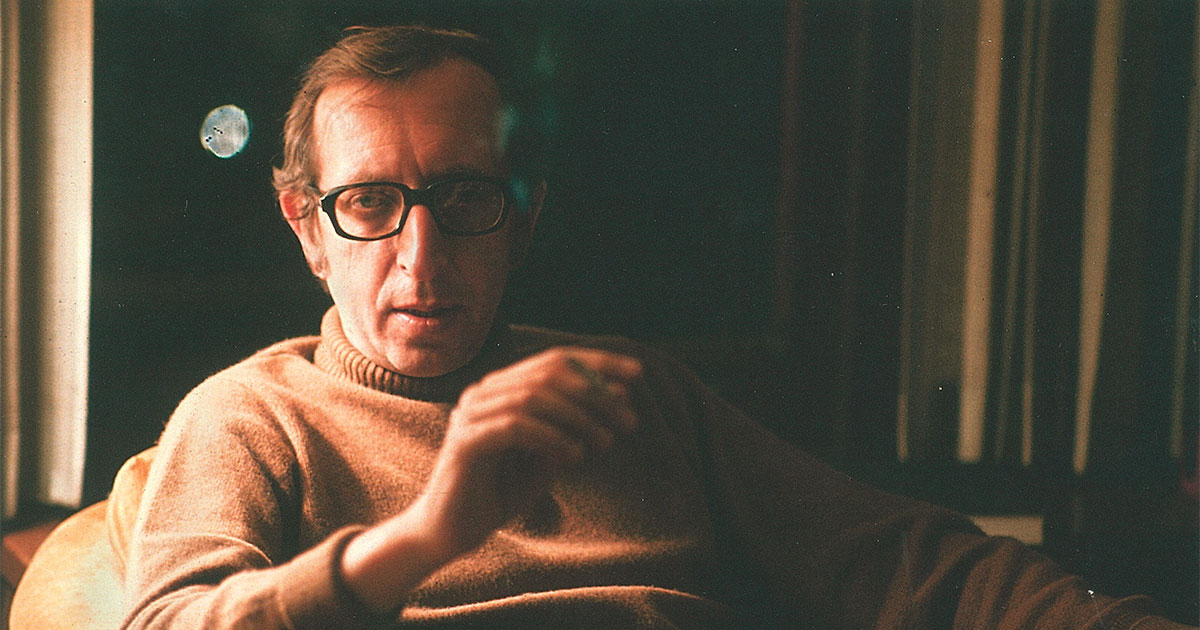

For almost 60 years, Jim Shellow has been one of the nation’s most formidable and revered criminal defense attorneys. A former president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL), he helped found the National Criminal Defense College and the precursor to the Legal Action Society in Milwaukee. His success challenging the definition of “cocaine” prompted Congress to amend federal law, and he has won acquittals in some of the country’s most notable cases. In recognition of all his work, Las Vegas even declared Jim Shellow Day – for the record, it’s October 26.

Despite all his success, Shellow’s walls aren’t filled with plaques and accolades or, for that matter, photographs with the famous. Instead, his home contains bookshelves packed with old, worn volumes and one beautiful old clock. It’s striking. And when you ask about it, Shellow says it was a gift from his mentor, and there’s a story that goes with it – of course there is.

Roots of Jim Shellow’s Legal Excellence

The clock originally belonged to William Scott Stewart, a person whose name is almost lost to history but who was a legend in his time. He wrote an acclaimed book on criminal defense,

Stewart on Trial Strategy,1 and the character Billy Flynn from the musical and film

Chicago was half-based on Stewart.2 Stewart’s years in practice in Chicago spanned the Great Fire’s aftermath through Prohibition. Beyond being a master of trial work and theatrics, he was a student of the law. Like all who excel in the courtroom, he had a complete command of the law and the rules of evidence, but he also saw the bigger questions and developed novel arguments. Stewart also committed himself to passing on the lawyer’s craft. He sought out and taught lawyers who he thought had promise; one of those was a younger attorney named Frank Oliver. It was to Oliver that Stewart gave his greatest lessons and the clock.

You only have to read a few chapters in

Your Witness, a collection of essays by Chicago criminal defense attorneys, to get a feel for Oliver’s singular talent.3 A brilliant individual, steeped in the classics, he was a master of trial work.4 According to those who saw him in action, Oliver developed his theory of the defense better than anyone, carrying it through pretrial motions to the jury, and if necessary, appeal.5

Oliver’s work ethic and technical genius were often overshadowed by his theatrics.6 To get a true taste of Oliver’s talent, one need only read the 10-page spread the

Chicago Lawyer did on one of his cross-examinations, which has rightfully been called a masterpiece.7

Like Stewart, Oliver wasn’t just concerned with his own practice. He believed in the adage that a rising tide lifts all boats, and so he set out to assist lawyers everywhere. Jim Shellow was one of the beneficiaries. Shellow came late to the practice of law. He grew up in Shorewood, just outside Milwaukee, and in high school was two years behind the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist. After a stint in the Navy during World War II, Shellow worked as an engineer for a military aircraft manufacturer. And when he tired of that, he became an accountant. Once he was married and a father to two children, he decided that he didn’t want to be a career accountant, so he settled on law school and enrolled at Marquette.

Law Review Piece Boosts a Budding Career. Shellow took to it, particularly criminal law. When it was time to write a law review note, he had just read an article in

Life magazineabout a mafia trial in New York. The defendants had been convicted of forming a conspiracy. The primary evidence was a meeting that they all attended – each had been under near-constant FBI surveillance – and then denied knowing it had even occurred.8 In response to the indictment, the group assembled a who’s who of New York’s and the country’s best attorneys, including the head of the ACLU. Despite the caliber of attorneys assembled, the group lost at trial and all were sentenced to prison.

The case intrigued Shellow, so he got a copy of the transcripts (almost 7,000 pages). After a full review, he felt that the verdict was an absolute injustice. Establishing a criminal conspiracy takes more than showing that certain individuals had all been at a meeting and lied about it – the government has to show that there was an actual agreement to violate the law; that is, the members were doing something more than just having tea. Committed to that view, he wrote his note in

Marquette Law Review on the case and colorfully titled it

The Tea Party Theory of Conspiracy.9

Convinced that the argument was misframed at trial, Shellow tried to convince the defense attorneys that they should push his argument on appeal. When his letters proved unpersuasive, he took a train to New York and asked for a meeting with one of the attorneys. Shellow had moxie. After hearing Shellow’s spiel, the lawyer told him to enjoy the sights and have a safe trip back to Milwaukee. Still convinced he was right, Shellow took another train (this time to Cleveland) to convince the renowned lawyer, Osmond Frankel, to hear him out. As the story goes, after an hour, Frankel was convinced. He immediately called the other attorneys and they changed the appellate brief to mirror Shellow’s theory. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, and all the convictions were overturned.10

The story has some true Hollywood appeal: a gutsy (and persistent) law student sees an angle that had escaped some of the best attorneys in the country. After traveling cross-country and having doors shut in his face, he finally convinces them to think differently – to adopt a new theory,

his theory. And then it wins! The clients are freed. Despite still having to finish his third year and not being able to speak in court, he’s a hero in one of the nation’s most well-known cases. But after graduation, Shellow couldn’t pack up and move to New York and trade on this new-found capital. He was married and his wife, Gilda, had another year in law school. He also had young children. In other words, his family was firmly settled in Milwaukee and he was staying. He would have to bloom where he was planted.

So he had to do what most do who feel a call toward criminal defense: he put up his shingle and took whatever case came through the door. And (like most) he initially floundered – badly. He didn’t have a more experienced partner to help him, didn’t know how much to charge to represent a client, and didn’t know what to do when it came to the actual courtroom. Abstract legal theory is one thing, cross-examining a witness is something else. As his struggles mounted, Shellow grew exasperated and discouraged. It was a rough time. All the genius and chutzpah it took for Shellow to take those train rides could have been lost to the realities of operating a criminal defense firm – constant and repeated failure. At this point, Shellow needed what all lawyers need: a mentor.

Lawyers who worked with Jim Shellow said two aspects of his practice stood out the most: his cross-examination skills and his command of the rules of evidence. Every win those lawyers experience is accompanied with a nod to Shellow’s influence and gift of time and friendship.

Need for Mentorship Spans All Professions and Times

Much has been written about the need for mentors and their value.11 The word “mentor” comes from

The Odyssey. It was the name the goddess Athena took when she befriended Telemachus, helping him grow into the man he was meant to be while his father (Odysseus) took 20 years to fight his way back to Ithaca from the Trojan War.12

Over time, the term has come to mean a person who takes interest in the career of another, one who imparts counsel,13 but such a watered-down description strips the word of its meaning. In its truest form, a mentor is someone who cares for another person (usually younger), who protects the mentee with sage advice, and who strives to get the very best out of the mentee while helping navigate and overcome life’s trials.14

Taking that form, a mentor’s value cannot be overstated. Some argue that effective mentoring is what breeds clusters of genius.15 It’s not pure chance that some of the greatest artists in western civilization all lived within 10 miles of Venice in the same 50-year period, one after another working in the same studios.16 Growing in expertise and ultimately mastery takes coaching and formation – with them, pitfalls are avoided and practice (in whatever venture) is made meaningful and ultimately transformative.17

A true expert who is committed to forming a newer attorney can shave years off the newer attorney’s learning curve.

A true expert who is committed to forming a newer attorney can shave years off the newer attorney’s learning curve. The greater the mentor’s commitment, the higher the student’s trajectory. Of course, intense reading and deliberate practice can (and do) help an attorney grow in mastery. But there is nothing like someone with experience allowing a newer lawyer simply to watch and listen. Nor is there a substitute for running through a transcript and asking the newer attorney what they were thinking with this or that question and then modeling how it could have been done better or reading a brief and helping refine the product. That type of mentoring demands a real commitment.

In this type of mentoring, newer attorneys see that small, deliberate steps in each specific situation separate the great from the merely good attorneys. Good lawyering is also a process of continual growth and failure – that is, after all, why we call it “a law practice.” In its truest (and best) form, mentoring helps the student to see the beauty of the attorney’s craft – revealing what excellent lawyering looks like and how rewarding it can be. The mentor provides a mental model for how all attorneys should conduct themselves.18

People who have had mentors likely remember the experience fondly, even if it was difficult; being corrected can hurt. The mentor shines a light on the student’s qualities and helps elevate the student’s craft. This process not only increases the student’s competency but also makes the practice of law more enjoyable and rewarding. Frank Oliver provided that to a young Jim Shellow.

Great Gifts from a Mentor

When Oliver and Shellow met, Oliver had never heard of

A Tea Party Theory of Conspiracy. He was waiting for his case to get called in the Milwaukee County Courthouse and watching a young Jim Shellow unsuccessfully defend a client on a prostitution charge. Shellow was being impaled by his own line of futile questioning. Whether Oliver recognized something special or was just being generous only he knew; but as Shellow left the courtroom, deflated, Oliver told him to sit down and watch – they would grab a drink afterward.

Oliver then conducted a clinic. What actually happened during Oliver’s cross-examination isn’t as important as what happened after. Oliver took Shellow out for that drink and asked him, “Who the hell taught you to ask questions like that?” When Shellow sheepishly explained his plight, Oliver told him to hop on the train and come down to Chicago later that week to watch some court.

Shellow did take the train to Chicago, where he sat in the back of the courtroom and watched Oliver and others. Afterward, he went with them to Binyon’s, a restaurant and bar, and he listened to these lawyers bat around their cases. Shellow wasn’t the only one soaking up Oliver’s genius. Other later legends of the Chicago bar were there, too, learning from and being formed by Oliver.19

Never content merely telling war stories, Oliver would assign reading, from Plato’s

Republic to nursery rhymes. Oliver believed that Plato’s works show how to develop a theory through questioning and to experience a speech and thought pattern with questions, and nursery rhymesshow the rhythm of an effective cross. Shellow has described this as a wonderful time, drinking beer and discussing the day’s reading and how it was reflected in what they’d just seen in court. Those days were crucial to Shellow’s development.

Hooked, Shellow kept coming and he kept learning. In response to Shellow’s willingness, Oliver’s mentoring went far beyond simply picking up the tab and running a reading group. Months later, Oliver had a six-week federal trial in North Dakota, and he invited Shellow to represent a co-defendant. During that trial, they rented a house and Oliver offered hundreds of little tips. This went beyond merely offering correction. Every day in court, he modeled a different level of lawyering, each level reflecting why Oliver was considered one of the very best.

In its truest (and best) form, mentoring helps the student to see the beauty of the attorney’s craft – revealing what excellent lawyering looks like and how rewarding it can be.

One Transforming Trial. After the prosecutor’s opening statement, Oliver stood up and moved for judgment of acquittal: the government’s opening (even if it was all true) wasn’t enough to convict. The judge agreed. But he let the prosecutor give a second opening. After the second opening statement, Oliver again stood up and made another motion for acquittal. The government still had not satisfied the elements. After a day’s recess, the judge gave the prosecutor a third try. And only then did he state an offense. So began Shellow’s immersion in how the law should be practiced.

Every night, Oliver got the transcript of the day’s proceeding and he would go over Shellow’s questions, picking them apart. He let Shellow know in which parts Shellow sounded clumsy or a witness had given him an answer that he failed to follow up on because he had not been listening to the witness. But the greatest lesson Shellow took from that experience happened midway through the trial.

Shellow floundered with an important witness: he was getting nowhere questioning the bank examiner. Among the case’s central questions was whether the transactions crossed the threshold for federal jurisdiction, and Shellow’s cross-examination had done nothing to further the defense’s argument. After telling Shellow to sit down, Oliver took out a dollar bill, marked it with an exhibit sticker, and gave it to the witness. He asked the witness how much he had given him: one dollar. Oliver then asked to borrow that dollar. The witness obliged. And then he said he’d lend it back to the bank examiner. How many dollars does he have? One dollar. He borrowed it again. And gave it back again, asking how many dollars there were. There was still only one dollar. Oliver then asked if that was repeated six million times, how many dollars would he have? Still one dollar. And thus, the transactions could not (and did not) clear the jurisdictional threshold amount. After getting that pivotal point out, Oliver asked the judge to withdraw that exhibit. He wanted Shellow to remember the lesson. The judge agreed. And Oliver handed Shellow that dollar – a dollar that is still in Shellow’s wallet, with the exhibit sticker on it.

That trial was the first of many that Oliver and Shellow would do together. Those experiences, and Oliver’s mentorship, helped forge Shellow into one of the great attorneys of the last century. Over his career, he won scores of acquittals. And after each, he’d call Oliver and thank him.

Flourish, Then Pass Along Mentoring

Shellow didn’t merely emulate Oliver’s approach to the courtroom; he also followed Oliver’s lead and pushed the law in new directions. Within five years after graduating, he had persuaded the Wisconsin Supreme Court to change the insanity defense,20 and within 10 years after graduation, Shellow had affected the law even more. He discovered that there were actually four isomers of cocaine, and the law only criminalized one of them.21 Given the lack of training that drug analysts had in organic chemistry, many (almost all) were incapable of distinguishing between the four and making certain that the substance before them met the legal definition.22 Shellow’s cross-examinations on that issue were so good that he was brought into cases around the country. This prompted the Fifth Circuit to observe in one opinion: “In the trial Shellow conducted what may properly be described as an extraordinarily able examination of the witnesses, based on his knowledge of the chemistry of cocaine.”23

His command of that topic was so great and his influence so far reaching that he wrote a book on it,The Cross Examination of an Analyst in a Drug Prosecution (2d ed. 2021). When the U.S. Supreme Court held that for Sixth Amendment confrontation purposes a drug analyst had to testify about his own work, it cited one of Shellow’s articles as evidence of the crucial flaws in the testing process that cross-examination can expose.24

Shellow’s influence goes far beyond the technical. His success and mark on the law included two cases going to the Supreme Court concerning rules-of-evidence questions25 and two cases to the Supreme Court concerning the First Amendment.26 Jim Walrath (who worked with Shellow for years) recalls Shellow’s prescience on where the law was headed: “He warned early on about how judicial activism would unfairly extend the reach of criminal laws. In the Supreme Court he opposed arguments that federal obscenity law convictions could be sustained through broad construction of the statutes: ‘I submit that’s legislation, that’s not adjudication.’”

Shellow’s arguments were not ignored. During one of those Supreme Court arguments, as Shellow was seated listening to the opposing side and waiting for his rebuttal, a Supreme Court page approached and handed him a note. It read: “Your argument is a testament to Shorewood High School’s greatness.” It was signed by then-Associate Justice Rehnquist. After reading the note, Shellow nodded to Rehnquist and slid it in his pocket.

Shellow also had a deep and unwavering commitment to justice and fighting for oppressed persons. In the 1960s he went to Mississippi to represent the Freedom Riders and brought his signature style to those courtrooms. After charges were dismissed for one of his clients, gunshots were fired into the house where Shellow was staying.27

Shellow represented individuals charged with crimes in connection with protesting the Vietnam War, including one of the Sterling Hall bombers, and he represented people who fought segregation, including Father James Groppi.28 He still has a copy of the

Milwaukee Journal headline announcing that the Court ordered Groppi’s immediate release from custody: “Justice Marshall Issues Order High Court Frees Groppi.”29 And in the mid-1970s, when hundreds of Native Americans were arrested in connection with the occupation of Wounded Knee, he and attorney Albert Krieger flew to South Dakota and organized the defense.30 They hunkered down for several months and took the cases to trial, pro bono. Eventually charges were dropped for all but two of the clients.

Shellow was also committed to improving the practice of criminal defense across the country. With Krieger, Shellow organized the first board of directors for the National Criminal Defense College. They had the idea of bringing the best attorneys in the country together with newer attorneys to learn the craft. For two weeks, attorney-students learned how to build trust with a client, as well as how to conduct voir dire, opening, direct examination, cross-examination, and closing. Shellow and others worked many hours every day teaching the students. The students learned by doing, which meant bringing in actors as witnesses and people off the street as potential jurors. Shellow, Krieger, and other teachers also made sure that the program was affordable – criminal defense is not lucrative, especially at the beginning. They endowed scholarships and underwrote the staff’s salary. It was a marvelous gift and thousands of students have graduated from the program since.

Shellow also sought out, hired, and trained many of the top attorneys in Wisconsin, giving them the same mentorship that he received from Frank Oliver. Among his best students was his longtime partner, Steve Glynn, who actually started out as a client – Shellow represented him when Glynn was a law student and was arrested for protesting the Vietnam War. After law school and a term clerking for U.S. District Court Judge James E. Doyle, Glynn was hired, and mentored, by Shellow and eventually became a name partner in Shellow’s firm.

Glynn provided a perfect complement to Shellow. As Glynn remarked, “Jim and Gilda were kind enough to make me a partner, but it was clearly still the Jim show.” That’s a bit of an overstatement: Glynn also is widely admired.31 He represented many high-profile clients and secured a string of six murder acquittals.32 He traces that success to the education Shellow provided. “The motion practice Jim drilled into us served me well as a defense lawyer. We both took immense pride in creative motions and loved sharing them with each other.”

One person fortunate to have worked for Shellow is Dean Strang (known, among other things, for representing Steven Avery, whose case was the subject of the docuseries

Making a Murderer). In the mid-1980s, Shellow had been brought on to handle a civil trial for the firm where Strang was an associate.33 Shellow had spent a very early morning reading all the pleadings and called Strang into the office at 6 a.m. that Saturday to go over what he’d just read. After a few hours together, Shellow was convinced Strang had a strong command of the case and let him argue the motion that Strang had briefed. When it was over, Shellow told him, “Great; now, let me tell you everything you did wrong.”

Shellow demanded that Strang and all the firm’s attorneys behave with the highest levels of decorum during every court appearance. The courtroom was no place for slouching, literally or figuratively. According to Strang, “Shellow lived by, and taught, a simple belief: in criminal defense, as in much of life, all the room is at the top; only the bottom is crowded.” Shellow demanded that attorneys working with him know the law, think creatively about the defense, and work tirelessly on how to persuade the judge and the jurors.

Lawyers who worked with Shellow said two aspects of his practice stood out the most: his cross-examination skills and his command of the rules of evidence. He was a true master of cross-examination – once cross-examining a witness for seven days. In another trial, the witness broke down and agreed that if he served on the jury he too wouldn’t believe his testimony. James Walrath recalled that Shellow would sometimes finish his cross-examinations of government experts – after they had admitted the inexactitude of their findings – by dismissively asking, “So, you hold that opinion simply because it’s good enough for government work?”

Shellow also had a deep command of the rules of evidence. He lived the adage: “No knowledge of the rules of evidence is too much; you must know and feel the rules, feel them in your very joints.”34 As U.S. District Judge J.P. Stadtmueller recalls: “Any time Jim Shellow was involved on behalf of a litigant, it was always a worthy endeavor. You could never be over prepared when you had Jim Shellow on the other side. There was so much to his efforts, especially with highly technical issues, whether chemical or the evidentiary escort for physical evidence.”

Shellow demanded the same commitment to the craft and to excellence in all its forms from all the lawyers who practiced with him; as a result, the attorneys who practiced under him thrived. In addition to Glynn, many of Wisconsin’s criminal defense attorneys trace their professional roots to Shellow. William Coffey was Shellow’s first partner after Gilda. Three of the four heads of the Federal Defenders Office were, as they call themselves, Shellow & Shellow alumni. These include Wisconsin’s first Federal Defender, Strang; his successor, Walrath; and the current Federal Defender, Craig Albee. In addition, Janice Roberts and Bill Theis, Chip Burke, Bob Friebert, and Rob Henak all had their start with and trace their success to working with Shellow. A full list of the lawyers who did a stint with Shellow’s firm would be too long for this article.

It’s tempting to think that when there’s an attorney as great and demanding as Jim Shellow, his demands would breed resentment. But the opposite is true. Every year on his birthday, the Shellow alums gather, and many of them stay in frequent contact with him and each other. At their core, Shellow’s demands were born out of a sense of helping everyone achieve their best – he truly cared for lawyer-students and that sentiment was reciprocated.

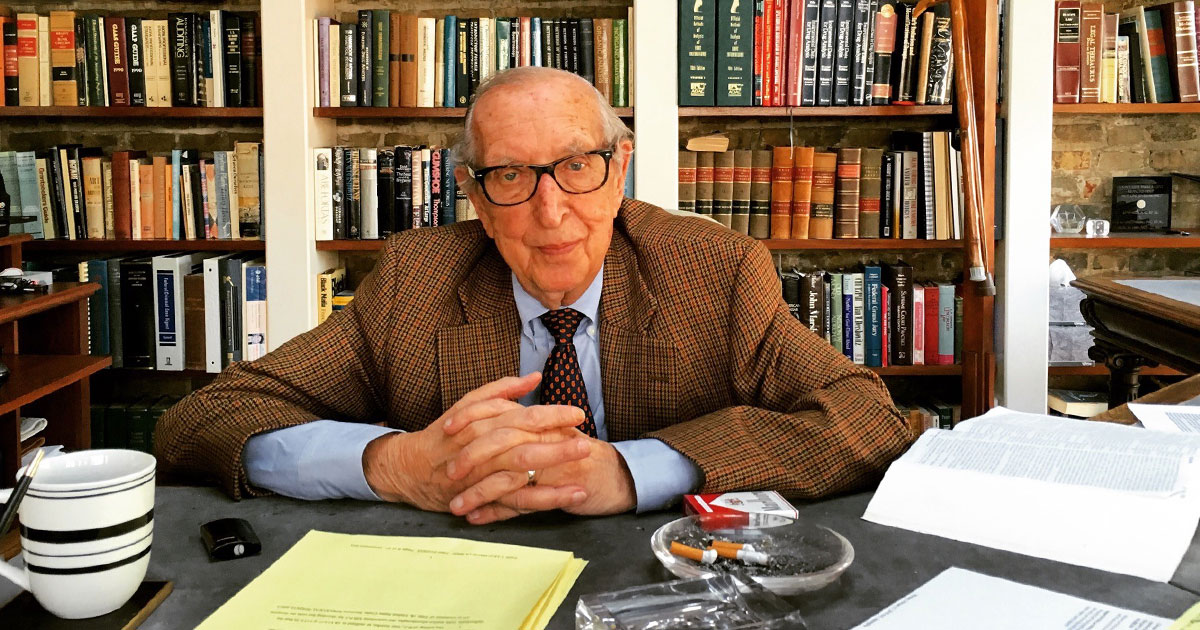

Retired from Practice But Not from Mentoring

When Shellow decided to wind up the practice, he sold his iconic office building and spent time with his wife, Gilda, in France.35 After her death, he could have contented himself with spending time with his daughters and relishing their success. His daughter Jill practices in New York and (among other things) takes on the burdens of federal death penalty work. His daughter Robin (who died in February 2021) carried on his legacy in Wisconsin, pushing the envelope and making a mark in Wisconsin’s state and federal courthouses. But Shellow wasn’t content with a quiet retirement.

He staked out an office inside Robin’s firm and gathered a group of younger attorneys around him (called the Shellow School by attendees). Rotating between his office, a restaurant, and later his condominium, the group would talk indictments, motions, and trial strategy. Shellow would ask probing questions. He’d read their briefs and then cover them with red ink, making them crisper and more persuasive. He would read the transcripts people brought, going over questions and, echoing Frank Oliver, he’d ask, “Who the hell taught you how to ask questions like that?”

For almost a decade, Shellow met with this younger generation of lawyers – beginning with Josh Uller, Tony Cotton, Chris Donovan, Joanna Perini, and Amelia Bizzaro, it eventually expanded to include Juval Scott, Ronnie Murray, Anderson Gansner, John Campion, and Gabriela Leija. They all learned to leave their pride at the door and to follow the Shellow way – to pursue excellence. He’d frequently invite them to his office to work through a case. He came to their trials to observe and teach and later critique – there was always a lot of critiquing.

Shellow’s influence on these attorneys extended to how they should approach the very practice of the law. As Chris Donovan recalls, he taught us “that all the room is at the top” and to “practice law and life with whimsy. And he used words like whimsy.” The demands he placed on us “to master the law and think creatively gave us the freedom to have fun.” Shellow modeled that this freedom to enjoy the law came from preparation and a command of the law’s rich history. As one student recalled: “He had a true appreciation for the law and he encouraged his students to learn it as well.”

One story in particular captures Shellow’s command of the law’s rich history. There is an anecdote from the eighteenth century about a property dispute involving a peasant’s claim. One of the lords dismissively asked the Irish barrister whether his client was familiar with the maxim, “Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos.” It means, “property rights extend from the sky to the bowels of the earth.”36 The lawyer replied: “why, of course, my Lord, the peasants of northern Ireland speak of little else.” It is a brilliant line, but one few (outside true students of the law) would know. In oral argument before the Seventh Circuit, Judge Richard A. Posner once asked Shellow if his client was familiar with the phrase, “de minimis non curat lex” (the law does not concern itself with trifles). Without missing a beat, Shellow responded “why, Your Honor, my clients speak of little else.” Familiar with the reference, Posner smiled broadly and was uncharacteristically quiet for the rest of the argument.

This command, confidence, and joy only come from someone who loves and knows the law and is deeply committed to it. As Josh Uller said, “Jim models how much fun there was to be had as a criminal defense lawyer. He was so committed to the process and so free in his practice, that it made you see what it meant to practice at a truly high level and just how rewarding it is.” And that’s because “being a criminal defense attorney isn’t for making money” but to “stand tall and proud in the face of injustice – to advocate for a person, your client.” Indeed, “Jim’s stories were always inspiring because they captured the best of what it meant to be a criminal defense attorney.”

Shellow also took a concrete interest in his students’ lives, passing on the same formation and friendship that Oliver offered to him. This has borne fruit in their professional lives. Many are considered top attorneys in the Milwaukee area. Shellow’s influence shines through in their work product. As Judge Stadtmueller observed when asked about Shellow’s impact on the criminal defense bar: “it is beyond measure.”

Conclusion

Just as Shellow called Oliver to thank him after every win, the same goes for those who attended Shellow School. Every win those attorneys experience is accompanied with a nod to Shellow’s influence and selfless gift of time and friendship. One attorney calls or emails after every win.

For most attorneys, their legacy is limited to their cases and their clients’ lives. While Jim Shellow certainly has made his mark on the law and his clients’ lives, his legacy is so much more. It’s a noble example of what it means to be committed to excellence. It is the example that William Scott Stewart set for Frank Oliver, the example that Oliver set for Shellow, and the example that Shellow set for everyone who was fortunate enough to count him as a friend and mentor. While Stewart’s clock will one day pass to another, the most important part of that legacy has been passed on to and works in the lives of countless others. And surely, those fortunate ones will pass on the lessons that Shellow taught and modeled to another generation. In that way, the clock will always tick.

Meet Our Contributors

What is the most rewarding part of your job?

The best part of my job is the relationships I have with my clients. I count many of them as close friends. And this job has given me a privileged place in their lives. I’ve cried with them, and I’ve celebrated with them – and not just over the case’s result. I’ve attended birthday parties and stood up in weddings; I’ve held their hands in the hospital, and I’ve spoken at their funerals.

The best part of my job is the relationships I have with my clients. I count many of them as close friends. And this job has given me a privileged place in their lives. I’ve cried with them, and I’ve celebrated with them – and not just over the case’s result. I’ve attended birthday parties and stood up in weddings; I’ve held their hands in the hospital, and I’ve spoken at their funerals.

This job has given me a window into one of life’s deepest realities – namely, everyone (absolutely everyone) is an individual worthy of dignity and respect, and no one can be defined by what they have done on their very worst day. Giving my clients the best representation I can is (in a small way) my contribution to that truth. But the job is so much more than merely representing my clients; it’s walking with them. That is truly the best part of my job.

Joseph A. Bugni,

Federal Defender Services of Wisconsin Inc., Madison

Become a contributor! Are you working on an interesting case? Have a practice tip to share? There are several ways to contribute to

Wisconsin Lawyer. To discuss a topic idea, contact Managing Editor Karlé Lester at (800) 444-9404, ext. 6127, or email

klester@wisbar.org. Check out our

writing and submission guidelines.

Endnotes

1 William Scott Stewart,

Stewart on Trial Strategy: Practical Suggestions to the Young Lawyer on How to Obtain and Hold Clients, How to Prepare and Try Lawsuits (Chicago: The Flood Co., 1940).

2

See Jill Schachner Chanen,

12 for the Stage, 98 ABA J. 38 (Aug. 2012) (“[The play] also features the unapologetically corrupt attorney Billy Flynn, a composite of W.W. O’Brien and William Scott Stewart, the flashy mob-connected Chicago lawyers who represented Gaertner and Annan.”);

see also The Fascinating Full Story of 2002’s Chicago, Musicoholics,

www.musicoholics.com/backstage-stories/the-fascinating-full-story-of-2002s-chicago/2.html (last visited Jan. 14, 2021).

3 Steven F. Molo & James R. Figliulo,

Your Witness (2008).

4

See, e.g., Stephen E. Henderson & Dean A. Strang,

Behind Bartkus:

A Flamboyant Lawyer, a Vindictive Judge, and the Untold Story of Double Jeopardy’s Dual Sovereignty, 24 New Crim. L. Rev. 498 (2021) (outlining Oliver’s many accomplishments).

5 “Frank’s grace and elegance set the standard for those who practice in the federal courts of Illinois. Frank did not try cases; he choreographed them. His magic and incandescent presence permeated our trials.”

Obituary of Frank W. Oliver, Chi. Tribune (accessed Jan. 14, 2021),

www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/chicagotribune/name/frank-oliver-obituary?pid=19474612 (quoting Jim Shellow).

6

See People ex rel. Woodward, 322 N.E.2d 240, 242 (Ill. App. Ct. 1975) (describing Oliver’s creative argument for refusing to participate in an in cameraconference);

United States v. Oliver, 470 F.2d 10 (7th Cir. 1972) (Oliver’s appeal from contempt charges stemming from theatrical stunt pulled with witness).

7

A Classic Defense, Chi. Lawyer, October 1983, pp. 11-21.

8

See United States v. Bonanno, 177 F. Supp. 106, 111–16 (S.D.N.Y. 1959).

9 James M. Shellow,

The Teaparty Theory of Conspiracy, 44 Marq. L. R. 73, 84 (1960).

10

United States v. Bufalino, 285 F.2d 408 (2d Cir. 1960).

11

See,

e.g., Cheryl E. Zuckerman,

Mentoring Matters: Teaching Law Students the Value of Mentoring Relationships, 20 Perspectives: Teaching Legal Res. & Writing 126 (2013); Allison R. Day,

The Importance of Having a Mentor in the Legal Profession, law.com/dailybusinessreview/2019/05/29/the-importance-of-having-a-mentor-in-the-legal-profession/?slreturn=20210014114850 (May 29, 2019); Robert Half,

The Value of Finding – and Being – a Mentor in the Legal Profession,

www.roberthalf.com/blog/management-tips/the-value-of-finding-and-being-a-mentor-in-the-legal-profession (last visited Jan. 14, 2021).

12 Homer,

Odyssey, Book 1;

see also American Heritage Dictionary (2d ed.) (defining

mentor as “Odysseus’ trusted counselor under whose disguise Athena became the guardian and teacher of Telemachus.”).

13

Mentor, American Heritage Dictionary (2d ed.) (“A wise and trusted counselor or teacher.”).

14 Ellen A. Fagenson,

The Mentor Advantage: Perceived Career/Job Experiences of Protégés Versus Non-protégés, J. of Organizational Behavior 10, no. 4 (1989): 309-20.

15 Eric Weiner,

The Geography of Genius (Simon & Schuster, 2016) (listing mentorship as one of the six conditions that fosters genius).

16

Id.

17 K. Anders Ericsson et al.,

The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance, Psychological Rev. 100, no. 3 (1993): 363.

18 Aristotle,

Nicomachean Ethics, Joe Sachs (trans.), Focus Philosophical Library (Pullins Press, 2002).

19 Nora Tooher,

Four Chicago Defense Lawyers in a League of Their Own, Chi. Syndicate (Apr. 13, 2008) (“[Rick Halprin] learned the legal ropes from Frank Oliver, a renowned Chicago criminal lawyer.”);

Obituary of Frank W. Oliver, Chi. Tribune (accessed Jan. 14, 2021),

www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/chicagotribune/name/frank-oliver-obituary?pid=19474612 (quoting Judith Halprin: “Those of us fortunate enough to come within his orbit experienced his extraordinary intellect, scholarship, elegance and imagination. In the process we learned from him how to be a trial lawyer.”); John Flynn Rooney,

Tom Durkin: Toiling to Keep the Criminal Justice System Honest, Leading Lawyers Network Mag. 24 (Dec. 2009) (“Durkin recounts that he learned the ins and outs of conducting cross-examinations from Oliver. Durkin observed him in court and joined him for drinks at Binyon’s, a former Loop watering hole.”),

www.durkinroberts.com/Leading_Lawyers_Network_TAD_Profile_December_2009.pdf.

20

State v. Shoffner, 31 Wis. 2d 412, 143 N.W.2d 458 (1966).

21 The Shellow Group,

Defense of Drug Prosecutions.

22 Defendant’s Motion for Disclosure of Exculpatory Evidence,

https://dc.fd.org/motions/alaska/discover/scientif.htm (last visited Feb. 4, 2022).

23

United States v. Bockius, 564 F.2d 1193 (5th Cir 1977).

24

Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, 557 U.S. 305, 320 (2009) (citing Shellow,

The Application of Daubert to the Identification of Drugs, 2 Shepard’s Expert & Scientific Evidence Quarterly 593, 600 (1995)).

25

Bourjailyv. United States, 483 U.S. 171 (1987).

26

United States v. Orito, 413 U.S. 139 (1973).

27

Shotgun Blasts Hit House With Reuss Lawyer Inside, N.Y. Times (Aug. 9, 1965),

www.nytimes.com/1965/08/09/archives/shotgun-blasts-hit-house-with-reuss-lawyer-inside.html.

28

Groppi v. Leslie, 311 F. Supp. 772 (W.D. Wis. 1970).

29 Milwaukee Journal, Oct. 28, 1969, headline.

30 Sam Roberts,

Albert Krieger, a Bulldog of the Criminal Defense Bar, Dies at 96, N.Y. Times (May 28, 2020).

31

www.milwaukeemag.com/LegalJudgments/.

32

www.superlawyers.com/wisconsin/article/the-lawyer-who-saw-the-lightning/38f72ea8-4a4e-439b-a1b5-2364f09c6884.html.

33

www.milwaukeemag.com/everybody-loves-dean-strang-making-a-murderer-cover-story/.

34 Lloyd Paul Stryker,

The Art of Advocacy: A Plea for the Renaissance of the Trial Lawyer, 91 (Simon & Schuster 1954).

35

https://urbanmilwaukee.com/2018/06/04/eyes-on-milwaukee-redevelopment-planned-for-milwaukee-news-building/.

36

See John G. Sprankling,

Owning the Centre of the Earth, 55 UCLA L.R. 979, 1024 n.282 (2008) (recounting this story).

» Cite this article:

95 Wis. Law. 38-46 (April 2022).