Conflicts over control of the “administrative state” have recently risen to the forefront of both federal and state political and legal discourse. In Wisconsin, conflict over the power of administrative agencies has been a subset of the broader conflicts between the governor and the legislature. In its recent opinion in Evers v. Marklein, the Wisconsin Supreme Court held that statutes that granted the legislature’s Joint Finance Committee the power to withhold its approval of – and therefore block – certain expenditures made by the Department of Natural Resources are unconstitutional.1 These expenditures were one of three issues that Governor Tony Evers and other petitioners asked the court to rule on in the petition for original action filed against members of the Wisconsin Legislature.2

In their petition, the governor and other petitioners also asked the court to address the authority of the legislature’s Joint Committee for Review of Administrative Rules (JCRAR) to delay or invalidate administrative rules promulgated by administrative agencies. As part of this request, the petitioners urged the court to revisit and overrule Martinez v. Department of Industry, Labor & Human Relations, a landmark opinion in which the court ruled that the legislature’s practice of “suspending” administrative rules issued by agencies was constitutionally permissible.3 In Evers v. Marklein, however, the court held the matter in abeyance, which suggests that it might address the issue before concluding the action.4 As of the writing of this article, the court has yet to indicate whether it plans to rule on the issue.5

Though Martinez has been cited frequently since it was issued in 1992, the history of the legislature’s power to suspend rules and the story behind Martinez have been largely forgotten. As questions of the separation of powers between the branches again make their way to the state’s highest court, this article revisits the history and events that gave rise to the case.

Legislature’s Involvement in Rulemaking in Wisconsin

Since shortly after executive branch agencies were first given the power to promulgate administrative rules in the early 20th century in Wisconsin, legislators have endeavored to police and limit that power.6 These efforts culminated in a short-lived provision, enacted in 1953, that granted the legislature the power to “disapprove” and consequently void an administrative rule by joint resolution.7

Michael E. Duchek, U.W. 2008, is senior legislative attorney and administrative rules counsel for the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, Madison. He is a member of the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Government Lawyers Division.

Michael E. Duchek, U.W. 2008, is senior legislative attorney and administrative rules counsel for the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, Madison. He is a member of the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Government Lawyers Division.

Legislative Disapproval Provision. The 1953 enactment also established a joint special legislative committee to study problems relating to rulemaking, including examining “the feasibility of placing limitations on rule-making powers of administrative agencies and of establishing a more uniform procedure for administrative rule making.”8 The study was a major undertaking,9 and a State Bar of Wisconsin committee was also appointed to assist the study committee.10 Among the matters examined by the special committee was the legislative disapproval provision – retention of the provision was initially contemplated, but the committee decided not to address it in its proposed bill until the issuance of an attorney general opinion requested by the Legislative Council.11

In the opinion, which was issued on the same date the final report for the committee was issued, Wisconsin Attorney General Vernon Thompson concluded that the provision was unconstitutional.12 Thompson’s opinion apparently sealed the fate of the provision: It was marked for repeal in the bill put forth by the study committee in the 1955 legislative session.

The bill was enacted within a matter of months, cementing the second major piece of Wisconsin’s Administrative Procedure Act, first enacted in 1943.13 Although the act contained many important provisions, including standards for rulemaking authority, uniform notice-and-comment requirements, and the creation of the Wisconsin Administrative Code and Register, the repeal of the disapproval power must have stung legislators seeking greater oversight over rules. However, the act did include one other item that would be the foundation for later efforts – the creation of a joint committee in the legislature to oversee rulemaking by administrative agencies.

Creation and Early History of JCRAR. The 1955 act gave the JCRAR advisory powers only, but a note in the final bill indicated that the committee’s advice was expected to carry considerable weight.14 Not surprisingly, however, legislators continued to pursue stronger oversight powers over administrative rules, and legislators began to eye the JCRAR as a vehicle. In 1959, the JCRAR was given the power to compel agencies to hold hearings on rule changes it suggested.15

Legislators continued to push for more, and a bill introduced in 1963, if passed, would have allowed the JCRAR to invalidate a rule by a vote of four of the committee’s five members. Citing his predecessor’s earlier opinion, Attorney General George Thompson concluded that this bill would likewise be unconstitutional.16

In 1964, Robert Haase (R-Marinette), who was then Speaker of the Assembly, indicated the mood of some legislators: “‘[T]he set of administrative rules is a bigger set of books than the statute books. You sometimes wonder who’s running the state of Wisconsin.’”17 Another lawmaker complained about “backdoor law making” and that a bill that had been killed in multiple sessions was being put into effect through an administrative rule.18

In 1965, several legislators proposed a constitutional amendment to specifically allow the suspension of rules by a joint committee of the legislature.19 This measure failed to advance, but the idea succeeded in a 1966 act that overhauled the structure and role of the legislative branch; as part of the act, the JCRAR was finally given the power to “suspend” administrative rules.20

The [1955] act did include one other item that would be the foundation for later efforts – the creation of a joint committee in the legislature to oversee rulemaking by administrative agencies.

JCRAR’s Power to Suspend Rules. The new suspension law included a feature that the earlier bills lacked – a requirement that, for a suspension by the JCRAR to become permanent, a bill in support of the suspension be introduced, put to a vote in the legislature as soon as possible, and enacted. This key requirement gave the governor the opportunity, as with other legislation, to veto the suspension, subject to veto override. Though the suspension power was seldom used at first, as time went on and additional changes to the suspension provision let the JCRAR suspend rules more easily, use of the suspension power increased dramatically.21

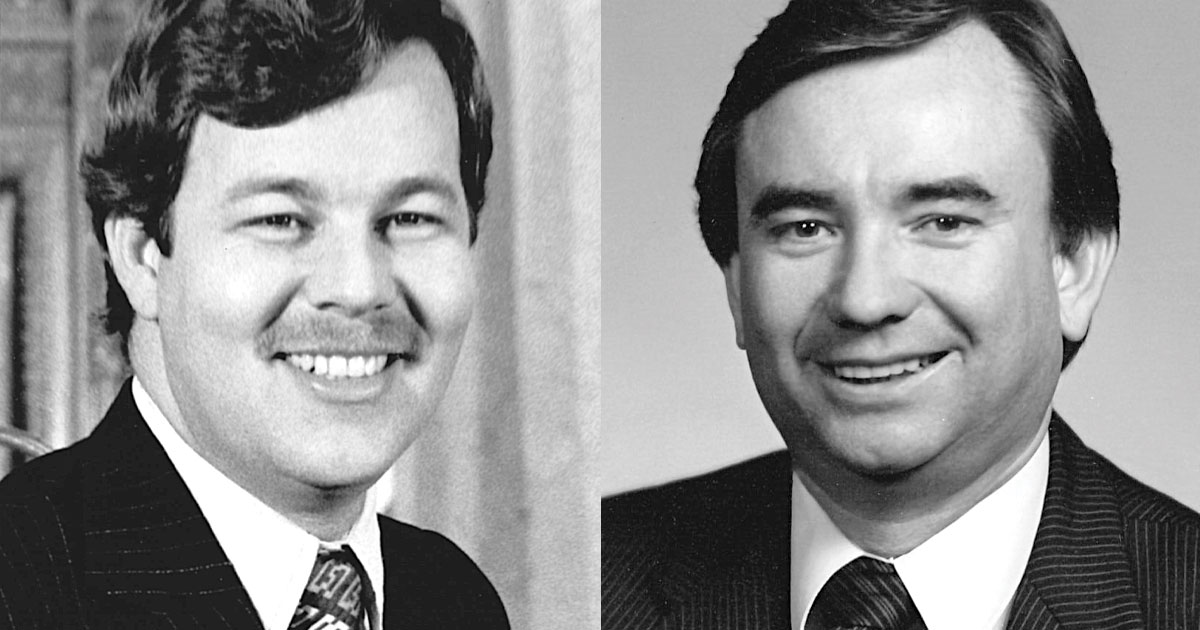

Ushering in this new era of legislative oversight was JCRAR chair Rep. Michael Ferrall (D-Racine), who presided over the “newly revitalized” committee.22 The more active oversight continued under Ferrall’s successor, Sen. David Berger (D-Milwaukee), who came to be known as “King David” when he chaired the committee23 and referred to it as a “poorman’s court.”24 A 1976 report observed the increasing rate of JCRAR hearings, with the committee not only suspending record numbers of rules but also engaging in various other oversight activities in the sessions that followed.25

As the committee’s power grew, concerns about the constitutionality of its power to suspend rules returned to the forefront. In a series of opinions issued in May 1974 that called into question the JCRAR’s existing powers, Attorney General Robert Warren concluded that the legislature’s power to void administrative rules was limited, again citing his predecessors’ similar conclusions.26

A legal challenge to JCRAR’s suspension power finally came in November 1975, when the organization Wisconsin’s Environmental Decade petitioned the supreme court to review a 1975 suspension of a rule promulgated by the Department of Industry, Labor & Human Relations (DILHR) setting thermal-performance standards for buildings.27 The case reportedly garnered attention from legislatures across the nation as observers awaited the court’s ruling.28 Ultimately, however, the bill required to uphold the suspension failed to pass in the assembly,29 and the court dismissed the action as moot, declining to take any further action in a short, unanimous opinion that offered no suggestion of the court’s views on the matter.30 It would be another 17 years before the supreme court would rule on the power of JCRAR to suspend a rule.

Meanwhile, legislators continued to seek greater opportunities to oversee not only administrative rules but also the rulemaking process. One proponent of this was Rep. Tommy Thompson (R-Sparta). During his legislative tenure in the late 1970s, Thompson, along with Sen. Berger, was instrumental in the enactment of the “Berger-Thompson” procedure for administrative rules,31 which cemented the role of the legislature in the rulemaking process and gave the JCRAR the power to “object” to proposed administrative rules before promulgation. If the JCRAR objected to a proposed rule, the rulemaking process would be put on hold, subject to a requirement that a bill be passed for the hold to be sustained, a process similar to that used for suspensions.

Legislators initially attempted to enact the procedure by adding it as an amendment to an unrelated bill in the 1977 session, but the bill was vetoed by Governor Martin Schreiber, a Democrat, who compared it to “adding War and Peace as a footnote to a short story.”32 After Schreiber lost the next election, legislators hoped his successor, Lee Dreyfus, a Republican, would be more amenable to allowing the Berger-Thompson provisions to become law. But a few weeks into Dreyfus’s term, Berger accused Dreyfus of breaking a campaign promise he had made to support the changes.33 Indeed, after the Berger-Thompson procedure was successfully added to the 1979 budget bill later that spring, Governor Dreyfus partially vetoed it, citing “basic separation of powers” and the prospect of a “legislative bureaucracy.”34 This time, however, the legislature was to have the last word: both houses of the legislature, in resounding bipartisan votes, acted to override the veto. It was the only successful veto override of the nearly four dozen partial vetoes Dreyfus issued on that budget bill.35

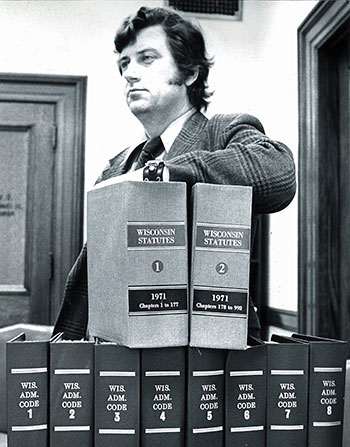

JCRAR Chair Rep. Michael Ferrall (D-Racine) comparing the two volumes of statutes with the eight binders of the Wisconsin Administrative Code. Photo: Wisconsin State Journal (1974)

The Martinez Suspension

In 1987, after nearly two decades of service in the legislature, Tommy Thompson began his first term as governor. When the 1989-90 legislative session commenced, Thompson found himself at odds with the legislature – in which Democrats had the majority – over the state minimum wage, which at that time was set by DILHR by administrative rule.

Proposal to Increase Wisconsin’s Minimum Wage. As the first major issue of the session, labor groups sought an increase in the minimum wage from $3.35 per hour, which had been the federally mandated minimum wage since 1981. Many businesses opposed the proposed increase, however, so Thompson settled on a compromise, agreeing to increase the minimum wage to $3.65 but with a lower “training wage” of $3.45 for “probationary” employees.36

Many labor groups, supported by most Democrats, objected to Thompson’s “two-tier” minimum wage proposal, with the head of the state AFL-CIO calling it an “insult to every minimum wage worker in the state.”37 Democrats in the legislature had made raising the minimum wage a priority of the session, with bills introduced in both houses seeking to set the minimum wage statutorily with guaranteed future increases and no separate training wage.

Thompson, however, pressed ahead with his more modest proposal using the rulemaking process. As the rule received review by labor committees in the legislature via the decade-old Berger-Thompson procedure, lawmakers pushed for removal of the lower training wage.38 Thompson did not budge, however, and quickly moved to have the rule finalized without the changes proposed by Democrats. He also vetoed the legislature’s minimum wage bill on June 30, 1989, just before the rule was to take effect.39 But Thompson did not have the last word on the matter.

Shortly after midnight on Saturday, July 1, 198940 – minutes after the rule had taken effect – the JCRAR convened to suspend the part of the rule setting a lower training wage.41 In doing so, the committee used a little-known aspect of its suspension power that allowed it to strike individual words and numbers.42 The convoluted suspension had been necessary because the rule had been rewritten beforehand to make it more difficult for the committee to partially suspend – a point that the Martinez petitioners later made note of in the brief they filed with the court.43 But the result was that the committee had found a way to neutralize the training wage by lowering the probationary period from 120 days to a mere three and making the period nonrepeating for subsequent employers.

Many reports drew parallels between the JCRAR’s partial suspension and the partial veto authority Thompson wielded as governor, which had recently been upheld by the supreme court44 and which was described as making the Wisconsin governor “the most powerful in the nation.”45 Observers also noted that Thompson, a vocal proponent of legislative oversight of agency rulemaking as a legislator, was now arguing against the oversight powers that he had once sought.46

Confusion soon arose as to whether the training wage was in effect, with the DILHR secretary advising employers that the JCRAR’s action was unconstitutional and that employers could feel free to pay the lower training wage if applicable.47 Democratic legislators cried foul; Rep. Peter Barca (D-Kenosha) admonished, “the problem is not only the question of the minimum wage but the authority of a non-elected bureaucrat to thwart the will of the Legislature.”48

As JCRAR Chair, Sen. David Berger (D-Milwaukee) worked with Rep. Tommy Thompson (R-Elroy) to enact legislative review requirements for administrative rules over the vetoes of two successive governors. Photo: Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau (1979)

Suit Filed Challenging Minimum Wage Rule. Jose Martinez and several other migrant farm workers who were often paid the minimum wage sued DILHR, alleging that they would rarely work for an employer beyond the rule’s probationary period and thus they would remain subject to the lower training wage.

The JCRAR and the Joint Committee on Legislative Organization soon moved to intervene in the action. Dane County Circuit Court Judge Susan Steingass issued a ruling upholding the rule suspension, concluding it was constitutionally valid. The ruling was quickly appealed to the court of appeals, which was also asked to stay the lower court’s ruling. The court of appeals declined to do so in a sharply worded order that was critical of DILHR and included a finding that the agency was unlikely to succeed on the merits in the matter.49

However, in a January 1991 opinion that must have come as a surprise, the court of appeals reversed and struck down the suspension as invalid, writing that the JCRAR’s action had constituted a violation of separation-of-powers principles. Unpersuaded by the fact that enactment of a bill was required to make a suspension permanent, the court of appeals concluded that even a temporary suspension of rules would allow the JCRAR to “[create] new law without presentment to the governor, thus denying the governor the power to veto the new law.”50

Supreme Court’s Opinion in Martinez. An appeal to the supreme court ensued, and on Jan. 15, 1992, exactly one year after the court of appeals issued its decision, the supreme court reversed the court of appeals. In a unanimous opinion written by Justice Donald Steinmetz, the supreme court held that the suspension power was constitutional.51 The court noted that administrative agencies are creatures of the legislature and that the law contained various checks and limitations on the JCRAR’s power, including that a bill would need to pass both houses of the legislature and be signed into law for a suspension to be made permanent.52 The court stressed that “[t]he full involvement of both houses of the legislature and the governor are critical elements of [the suspension process], and these elements distinguish Wisconsin from the statutory schemes found to violate separation of powers doctrines in other states.”53

Not present in the court’s opinion, however, was any analysis of the procedures, timelines, or standards the JCRAR and the legislature should be held to when suspending rules. Nonetheless, the court had finally ruled on the important separation-of-powers issue and had done so despite that the issue was arguably again moot: Neither bill introduced to make the suspension permanent was ultimately enacted. Within a few months, another rule had been promulgated to match a 1990 increase in the federal minimum wage to $3.80.54

The Martinez Legacy

The supreme court’s decision in Martinez, which left many questions unanswered, remains, as of August 2024, the most recent and only significant word on the legislature’s power to invalidate administrative rules. In Service Employees International Union (SEIU) v. Vos, the supreme court briefly discussed Martinez when upholding against a facial challenge a provision enacted in 2018 that authorized the JCRAR to suspend a rule multiple times. In his opinion for the majority on the issue, Justice Brian Hagedorn wrote, “Under Martinez, an endless suspension of rules could not stand; there exists at least some required end point after which bicameral passage and presentment to the governor must occur.”55

Although the law allowing the legislature to suspend administrative rules has been changed in numerous ways since its enactment, the core features of the laws have remained intact and continue to be used, especially in times of divided government.56 As observers await the supreme court’s decision on whether to revisit its holding in Martinez as part of the Evers v. Marklein action, this recounting provides context for the court’s groundbreaking 1992 decision.

Endnotes

1 Evers v. Marklein, 2024 WI 31, ¶¶ 2, 19, 412 Wis. 2d 525, 8 N.W.3d 395.

2 Pet. for Orig. Action, Evers v. Marklein, No. 2023AP2020-OA, ¶¶ 4-6.

3 Id. ¶ 110; see Martinez v. Department of Indus., Lab. & Hum. Rels., 165 Wis. 2d 687, 478 N.W.2d 582 (1992).

4 Order dated Feb. 2, 2024, Evers v. Marklein, No. 2023AP2020-OA, 2. The other issue that the court held in abeyance concerned the authority of the legislature’s Joint Committee on Employment Relations regarding pay raises for University of Wisconsin System employees.

5 On July 5, 2024, the same day that the supreme court issued its opinion in Evers v. Marklein, the court issued an order “that the parties file simultaneous legal memoranda by July 26, 2024, discussing the impact of today’s decision, if any, on whether the court should grant review of the second and/or third issues set forth in the petition for leave to commence an original action.” In their memorandum, filed that day, the petitioners renewed their request for the court to revisit the rulemaking issue and overrule Martinez. Pet’r’s Suppl. Mem. Regarding Issues Held in Abeyance, Evers v. Marklein, No. 2023AP2020-OA.

6 An extreme example, 1941 Wis. S.B. 306, would have prohibited all rulemaking by state agencies, voided all existing rules, and dismissed actions and proceedings brought under any rules. However, the bill reportedly garnered “marked indifference,” and even the author of the bill, Sen. Jesse Peters (R-Hartford), was reportedly unwilling to speak in favor of it at a judiciary committee hearing. “Peters Bill to Abolish State Orders Snubbed,” Cap. Times, April 16, 1941.

7 Wis. Stat. § 227.031 (1953) (created by Chapter 331, Laws of 1953). Joint resolutions, unlike bills, require action only by the state senate and assembly and are not subject to approval or veto by the governor.

8 Wis. Stat. § 227.001(1) (1953) (created by Chapter 331, Laws of 1953). See Orin L. Helstad & Earl Sachse, A Study of Administrative Rule Making in Wisconsin, 1954 Wis. L. Rev. 368 (1954).

9 Earl Sachse, the Legislative Council secretary, told the committee members that the committee had been provided “a liberal appropriation for research” that would cover all 48 states. “Rule Making Study to Begin,” Milwaukee J., Sept. 11, 1953.

10 Robert M. Reiser, “The Legislature Studies Administrative Rule Making,” Wis. Bar Bull., Feb. 1955, at 25.

11 See Report of the Wisconsin Legislative Council, Vol. II, Part 1, Conclusions and Recommendations of the Committee on Administrative Rule Making 7 (Dec. 28, 1954).

12 43 Wis. Op. Att’y Gen. 350 (1954). Although the notes in the bill made no reference to the provision, Helstad’s account indicates that it was repealed in accordance with the attorney general’s conclusion that it was unconstitutional. Helstad & Sachse, supra note 8, at 428.

13 Chapter 221, Laws of 1955, was dubbed a “legislative achievement” for its comprehensive effort at addressing rulemaking. “A Legislative Achievement,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, July 16, 1955. Wisconsin’s initial enactment of an administrative procedure act, Chapter 375, Laws of 1943, was based on what became the Model State Administrative Procedure Act but left rulemaking largely unaddressed.

14 Explanatory notes were included in the bill, 1955 Wis. S.B. 5, which became Chapter 221, Laws of 1955. See also Wis. Stat. § 227.041 (1955).

15 Chapter 537, Laws of 1959.

16 52 Wis. Op. Att’y Gen. 423 (1963).

17 “State Rules to Be Probed,” Milwaukee J., March 31, 1964.

18 Id.

19 S.J.R 72, 1965 Leg. (Wis. 1965).

20 Chapter 659, Laws of 1965, § 1. The suspension language was initially included in Wis. Stat. section 13.56(2) (1965) and required a vote of six of the committee’s then nine members.

21 Chapter 162, Laws of 1973, lowered the threshold for the JCRAR, then a nine-member committee, to suspend a rule from six votes to a majority of members present, a key change that ushered in greater use of the suspension power. Chapter 29, Laws of 1977, subsequentlymade other changes to the JCRAR, including adding an additional senator to divide the composition of the JCRAR equally between the two houses, as it remains today.

22 “Administrative ‘Laws’ to get Review,” Wisconsin State J., April 29, 1974.

23 Dick Wheeler, “Sen. Berger Building a Power Base,” Sheboygan Press, Aug. 8, 1979. “To be sure, Berger and his operation of [the JCRAR] borders on demagoguery, but not without justification.” Id.

24 Joint Committee for Review of Administrative Rules, Biennial Report 1977-1978, letter opposite front cover dated Jan. 1979.

25 Richard A. Eggleston, “Rules Can Make Life Miserable,” Wisconsin State J., Aug. 3, 1976. See also “A Battle for Power in Fight Over Rules,” Milwaukee J., April 24, 1978. Records show that the JCRAR suspended a rule only once between 1965 and 1970, nine times between 1971 and 1976, and 13 times in the 1977-78 session alone. The JCRAR reports from this era also document other oversight, research, and legislative projects pursued by the JCRAR, including the appointment of subcommittees. However, suspension activity dropped in the sessions that followed, with only four suspensions occurring between 1979 and 1984.

26 63 Wis. Op. Att’y Gen 159 (1974); 63 Wis. Op. Att’y Gen 168 (1974); 63 Wis. Op. Att’y Gen 173 (1974).

27 “Group Challenges Power of Legislative Unit,” Cap. Times, Nov. 25, 1975. The department was dropped from the case by stipulation, but Attorney General Bronson La Follette was given amicus status and filed a brief in opposition to the suspension.

28 Whitney Gould, “Rules Panel in Court Fight Over Powers,” Cap. Times, April 13, 1976.

29 The bills were 1975 Wis. S.B. 665, which passed the senate, and 1975 Wis. A.B. 1192.

30 Stateex rel. Wis. Env’t Decade v. Joint Comm. for Rev. of Admin. Rules, 73 Wis. 2d 234, 243 N.W.2d 497 (1976).

31 See Joint Committee for Review of Administrative Rules, Biennial Report, 1977-1978, at 161-62. For one account of Thompson’s efforts, see William E. Hauda, “Persistent Assemblymen Try to Limit Bureaucratic Rules,” Wisconsin State J., May 17, 1977.

32 Gov. Martin J. Schreiber, Veto Message for 1977 SB 199, at 1 (May 26, 1978). The full message, with portents of the ills that would occur as a result of legislative involvement in rulemaking, summarizes the competing views of the legislature and a governor with respect to the administrative rules process.

33 “Dreyfus Broke Vow, Berger Says,” Milwaukee J., Jan. 27, 1979.

34 Gov. Lee Dreyfus, Veto Message for 1979 SB 79, July 25, 1979, at 9, 10.

35 Chapter 34, Laws of 1979. The override votes were 29-4 in the senate and 85-13 in the assembly. Today, the objection process is codified in Wis. Stat. section 227.19. There are similarities and differences between the objection process and the suspension process.

36 Arthur Srb, “Democrats Ready for Minimum-Wage Showdown,” Wisconsin State J., July 6, 1989.

37 “Lawmakers Bypassed on Wage Hike,” Appleton Post Crescent, Feb. 5, 1989.

38 402B Wis. Admin. Reg. 24 (June 30, 1989).

39 Gov. Tommy G. Thompson, Veto Message for 1989 Assembly Bill 1 (June 30, 1989). The rule, CR 89-20, was finalized in May and given a July 1, 1989, effective date.

40 Neil H. Shively, “Victory Seen on Joint Panel,” Milwaukee Sentinel, Nov. 27, 1991.

41 Joint Committee for Review of Administrative Rules Committee Record, July 1, 1989.

42 Notice of Suspension of an Administrative Rule, 403A Wis. Admin. Reg. 72 (July 15, 1989).

43 Br. of Appellants, Martinez v. Department of Indus., Lab. & Hum. Rels., No. 90-1266, 13.

44 Stateex rel. Wis. Senate v. Thompson, 144 Wis. 2d 429, 424 N.W.2d 385 (1988).

45 Matt Pommer, “Governor’s Executive Power Grab Moves State Closer to Imperialism,” Cap. Times, July 10, 1989; see also Shively, supra note 40.

46 Arthur L. Srb, “Governor Sings New Tune on Legislative Oversight,” Cap. Times, July 7, 1989; see also Pommer, supra note 45.

47 Dep’t of Indus., Lab. & Hum. Rels. Press Release, July 5, 1989, as reported in Srb, supra note 36.

48 Srb, supra note 36.

49 Order dated Aug. 2, 1990, Martinez v. Department of Indus., Lab. & Hum. Rels., No. 90-1266.

50 Martinez v. Department of Indus., Lab. & Hum. Rels., 160 Wis. 2d 272, 280, 466 N.W.2d 189 (Ct. App. 1991), rev’d, 165 Wis. 2d 687, 478 N.W.2d 582 (1992).

51 Martinez, 165 Wis. 2d 687.

52 Id. at 699.

53 Id. at 700.

54 See CR 89-197, which became effective April 1, 1990. The bills to uphold the suspension were 1989 Wis. S.B. 254 and 1989 Wis. A.B. 471. The senate bill passed in its chamber of origin, but neither bill passed in the assembly. The court of appeals suggested this was because the federal minimum wage had been raised by November 1989, somewhat obviating the need for the legislature to act on the bills. Martinez, 160 Wis. 2d at 280.See also U.S. Dep’t of Lab., History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates Under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938–2009, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/history/chart (last visited Aug 9, 2024).

55 Service Emps. Int’l Union (SEIU) v. Vos, 2020 WI 67, ¶¶ 12, 81, 393 Wis. 2d 38, 946 N.W.2d 35.

56 See Wis. Stat. §§ 227.19, 227.26(2).

» Cite this article: 97 Wis. Law. 30-36 (September 2024).