Almost 10 years ago, litigation attorneys sounded the alarm by predicting that litigation involving the disclosure of electronically stored information (ESI) would engulf the discovery process, especially in complex cases. Many plaintiffs’ attorneys viewed electronic discovery as an opportunity to leverage settlement, and the lawsuit itself, by seeking broad fields of electronic data at considerable cost to the defense. In response to these requests, defendants’ attorneys emphasized limited alternatives that did not produce meaningful, responsive information.

Almost 10 years ago, litigation attorneys sounded the alarm by predicting that litigation involving the disclosure of electronically stored information (ESI) would engulf the discovery process, especially in complex cases. Many plaintiffs’ attorneys viewed electronic discovery as an opportunity to leverage settlement, and the lawsuit itself, by seeking broad fields of electronic data at considerable cost to the defense. In response to these requests, defendants’ attorneys emphasized limited alternatives that did not produce meaningful, responsive information.

As this cat-and-mouse game unfolded, parties often overlooked the need for a coordinated electronic discovery plan that anticipates and solves problems in the e-discovery process. This is a missed opportunity for litigants to address critical issues, such as the early identification and preservation of potentially relevant electronic data and the authentication and admissibility of that data at trial. Even today, many competent attorneys profess ignorance about these questions and openly admit that e-discovery is not a central consideration in most of their discovery plans.

This article proposes a template for an electronic discovery plan that is suitable for plaintiffs’ and defense lawyers. By necessity, this article emphasizes the need for early cooperation as a necessary component of an efficient electronic discovery plan, grounded in the meet-and-confer requirements in Wisconsin’s Rules of Civil Procedure. From there, this article provides the template for an electronic discovery plan for plaintiffs and defendants that ensures compliance with existing discovery obligations and provides guidance for the discovery of electronic data in the ever-changing digital age.

Introduction to ESI

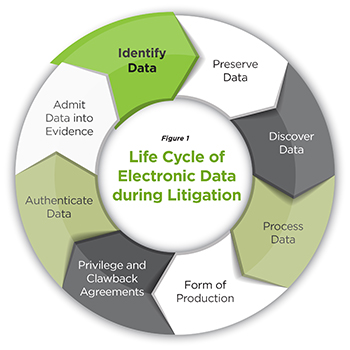

In general terms, ESI is nothing new. Before their recent amendment, the Wisconsin Rules of Civil Procedure contemplated that electronic data stored in a fixed tangible form was on equal footing with paper “documents.” While the recent amendments confirm that electronic data is a “document” governed by the rules of discovery, this has never been an issue.1 Instead, the question is how counsel adjusts her strategy to the unique technical features of ESI. To answer this question, it is necessary to examine the life cycle of electronic data during the litigation process (see Figure 1).

These obligations are similar, if not identical, to the process that applies in the discovery of traditional, paper documents. The difference rests in the complexity and expense involved in processing the information. This article focuses on a plan that recognizes the unique technology that accompanies the discovery of electronic data. In all cases, this process starts with the obligation to preserve ESI through a properly drawn litigation hold.

Identification and Preservation of Data: Spoliation and the Litigation Hold

For many years, courts have recognized that entities have an affirmative duty to preserve potentially relevant information in anticipation of litigation or face sanctions for spoliation of evidence.2 This obligation applies equally to ESI, which can be more difficult to identify and preserve due to the technology involved. Although Wisconsin has not weighed in on this specific issue, the most reliable formulation of the duty to preserve is set forth below:

When litigation is reasonably anticipated or at the commencement of litigation, counsel must issue a litigation hold, which should be periodically re-issued to keep it fresh in the minds of employees and to make new employees aware of it.

Counsel should identify the persons who are “likely to have relevant information” and communicate directly with these “key players” to ensure they are aware of their duty to preserve relevant information. These key players are the people identified in a party’s initial disclosures and any supplementation thereof.

Counsel have a duty to instruct all employees of the client to produce electronic copies of their relevant active files and to identify, segregate, and safely store relevant backup tapes. The court went so far as to suggest that, in an appropriate case, counsel take physical custody of relevant backup tapes to safeguard the information.3

Preserving information relevant to a pending lawsuit is important for many reasons. If a party fails to preserve evidence after litigation is reasonably anticipated, this failure can lead to serious punitive consequences for evidence spoliation.4 These consequences can include monetary sanctions, awards of attorney fees and costs for the price of investigating and litigating document destruction, and litigation consequences such as default judgments, dismissal of certain claims or defenses, or court instructions allowing a jury to draw adverse inferences about what destroyed evidence would have shown.5

Figure 1

Life-cycle of Electronic Data during Litigation

Preservation obligations for electronic data are no different than those that apply to traditional, paper documents, because the duty to avoid spoliation is well settled in the law. The only difference is the procedures that must be followed due to the unique, transitory nature of ESI, which theoretically can be destroyed with the push of a button. Counsel must institute a litigation hold that identifies and preserves all relevant electronic data when litigation is reasonably foreseeable.6 This raises questions regarding the timing of the obligation, its time frame, and scope. In many cases, once the duty to preserve is triggered, the time frame of the preservation obligation will go back many years and require the preservation of different sources of electronic data.7 Defense counsel, in particular, must be cognizant of this obligation and its nuances.

Compliance with preservation obligations is a two-way street. Plaintiffs often forget that they also maintain electronic records that could be relevant to the dispute. At the beginning of the case, plaintiff’s counsel must execute a litigation hold that identifies and preserves electronic data that is relevant to the potential claims and defenses. The litigation hold should be specifically crafted to the facts by defining the case, identifying relevant information, and explaining preservation obligations in some detail. Counsel should take immediate steps to quarantine these records once litigation is foreseeable.

After both the plaintiff and the defense have satisfied the preservation obligation, each party should prepare and discuss a preservation agreement that is tied to a number of basic objectives including, but not limited to, early identification of most likely sources of ESI, and the continued preservation of ESI pursuant to a litigation hold that is properly executed and carefully documented. This preservation plan can be negotiated before or during the meet-and-confer session, but it should be one of the first steps in the process if there is doubt about the preservation of electronic discovery.

Meet-And-Confer Process

The meet-and-confer process is vital to a successful electronic discovery plan.8 A productive ESI discovery plan requires counsel to set aside the role of zealous advocate in favor of an exchange of information that accelerates the discovery process. It is a fool’s errand to bypass the opportunity presented by a robust meet-and-confer session in a case involving substantial electronic discovery. This is an opportunity to learn about the opponent’s data systems and preservation efforts and the existence of litigation hold and document retention policies that might shape the e-discovery process. If the meet-and-confer session is conducted properly, an attorney has nothing to lose by participating in good faith. The key is early planning and preparation.9

Figure 2

Discussion Topics for the Meet-and-Confer Conference

During the meet-and-confer, attorneys should discuss the topics set forth in the Wisconsin Rules of Civil Procedure and all the issues listed below:

Processing Data

- Document review protocol: manual or digital review for relevance, privilege, and confidentiality

- Search terms: agreed-on process: Search terms? Custodians? Time-frames? Sources: Databases? Unstructured data sources? E-mail servers? Legacy data? Back up data?

Form of Production

- Most common forms of production (pdf, native format, TIFF images), including disclosure of metadata, de-duplication obligations, production of structured data, production of inaccessible data, and Bates-stamping protocol

Negotiated Protections

- Disclosure of document retention plans and policies

- Execution of documents that may be necessary to protect privileged information that is inadvertently disclosed during the litigation, including clawback agreements and privilege logs

- Use of a protective order to shield confidential information

Efficient Use of Discovery Tools

- Use of discovery tools to avoid cost shifting or resolve cost-shifting issues

- Implementation of a discovery plan that authenticates ESI, through proof or stipulation, and identifies those documents that the circuit court must authenticate

Topics for the Meet and Confer. The topics for a meet-and-confer session should not be confined to those set forth in the Wisconsin Rules of Civil Procedure. During the meet-and-confer conference, counsel should prepare to address all the issues indicated in Figure 2.

Preparation for the Meet and Confer. In many cases, the results of the parties’ meet and confer could be scrutinized by the court. Here, a discovery plan is likely to be more persuasive if counsel can demonstrate that it is supported by actual facts regarding the information requested and the actual costs involved.10 Conclusory assertions that requested discovery is too burdensome are unlikely to prevail absent underlying facts. To the extent possible, counsel should identify key custodians and consider the use of search terms to alleviate cost while maximizing the potential response to the plaintiff’s search. Under all circumstances, preparation and good faith will position counsel to obtain as much discoverable information as possible.

Defense counsel must be prepared to reveal his client’s preservation efforts at the meet-and-confer session. In addition, defense counsel should be prepared to identify legacy or back-up data that is inaccessible to set the stage for cost-shifting arguments as the case proceeds. If possible, defense counsel should have information about the cost and burden of searching these records, along with any other difficulties presented by the company’s computer system for search purposes. If crucial data is located in one of these repositories, the parties should attempt to negotiate a resolution of this dispute or agree to bring the matter to the court’s attention. Unlike the plaintiff’s counsel, who should be prepared to demonstrate an efficient plan for obtaining ESI that will not cause an undue burden, it will be common for the defense to explain expensive obstacles posed by the plaintiff’s electronic discovery plan to set the stage for further limits on discovery. In preparing a proposal for discovery, defense counsel should consider the following:11

The volume of data reasonable to review in the time frame allotted by the court and the client’s financial restrictions;

The number of (and sources) from whom the client might need to collect data if the plaintiff issues broad discovery requests;

Arguments for limiting the custodian list;

Methods for phasing discovery;

Methods for searching data, including date restrictions, search terms, and other restrictions such as privilege; and

The timing for exchange of privilege logs.

In many situations, the volume of data in the case can be appropriately limited with keyword or concept searches or a computer-assisted review tool. Although search terms often are an effective means of identifying responsive documents and lessening the overall burden of the review, courts have recognized that their use can lead to underinclusive or overinclusive results and must be employed cautiously.12 Courts have also begun to investigate and even endorse use of analytics technology to identify potentially relevant information through “predictive” or “automated” coding.13

Regardless of the tools used, it is important to interview custodians and determine which core custodians’ data really must be collected and reviewed – whether by a computer or by attorneys. If the collection is large and the discovery requests broad, any method used will be expensive, and the parties should focus on limiting the core data set. Failure to obtain agreement with opposing counsel on the method for processing data or, absent agreement, the failure to take reasonable steps to collect and produce core relevant data can lead to sanctions.14

The meet-and-confer process can be a lethal tool for a lawyer who has experience dealing with ESI and is well prepared. Sometimes, opposing counsel will appear unprepared for the meet-and-confer process or otherwise refuse to participate in a good-faith exchange of information. It is not uncommon for counsel to rely on assertions of privilege or conclusory allegations of undue burden in an effort to conceal their ignorance or avoid their meet-and-confer obligations. Under these circumstances, counsel should file an immediate motion with the court to compel the other party’s participation in the meet-and-confer process, which then will unfold under the court’s supervision.

Processing and Reviewing

Before producing records, the plaintiff must process the data that he seeks to preserve pursuant to his client’s ongoing litigation-hold obligation. The first step is locating the potentially responsive data and securing it for future use. Depending on the quantity, the next step is to review the document to determine whether it is privileged or contains confidential information that is governed by a protective order. Once the privileged documents have been withheld and recorded on a privilege log, they should be set aside and preserved, as should the proprietary information, if any, that was produced and appropriately labeled pursuant to the protective order. Finally, counsel should conduct a relevance review to determine whether certain documents are nonresponsive or irrelevant to the case. These documents should also be set aside, if necessary, for future use.

Timothy D. Edwards, Wayne State 1989, is of counsel at Cullen Weston Pines & Bach LLP, Madison, and an adjunct lecturer at the U.W. Law School, where he has taught for almost 15 years. His practice focuses on employment law, commercial litigation, and electronic discovery.

Timothy D. Edwards, Wayne State 1989, is of counsel at Cullen Weston Pines & Bach LLP, Madison, and an adjunct lecturer at the U.W. Law School, where he has taught for almost 15 years. His practice focuses on employment law, commercial litigation, and electronic discovery.

The document review process can be much more onerous for defense counsel, who often has access to more electronic data than does the plaintiff’s attorney. Depending on the size of the organization, processing ESI can be a daunting task. This is especially true at the early stages of the review process, when responsive documents are identified for production.

In many situations, opening files one-by-one in their many different source applications is impractical and might result in the destruction of metadata. In these cases, it is necessary to load the ESI into a platform that is searchable and to apply a review tool that can perform a variety of functions, including file extraction, removal of system files, and de-duplication. After the relevant data set is culled from the original production set, agreed-on search terms are applied and responsive documents are processed for final review in the agreed-on format. This process will often require the assistance of in-house information technology (IT) employees or a qualified vendor.

Clawback provisions can ameliorate the consequences of inadvertent disclosures of privileged information in certain instances. Assume that plaintiff’s counsel reviewed more than 100,000 documents after filing a lawsuit against a company’s CEO. By mistake, counsel disclosed a document in which his client made very damaging statements that directly affected the strength of her case. If the parties reached an agreement during their discovery plan that includes an order that protects against the waiver of privilege, it is possible to retrieve the document and preserve the privilege without further issue.15 To do so, in the example, plaintiff’s counsel must immediately give notice to defense counsel, in writing, that the document was produced inadvertently after reasonable steps were taken to prevent its disclosure. At that time, defense counsel must promptly return, sequester, or destroy the document.

Clawback provisions provide important protection against the waiver of the attorney-client privilege that results from inadvertence due to the sheer volume of data involved. They also demonstrate how planning, at the meet-and-confer stage, can prevent significant problems that result from the volume of data that is often reviewed in complex e-discovery cases.

Production

Form of Production. Production is the next step in the ESI life cycle after the information has been preserved, collected, and processed. The Wisconsin Rules of Civil Procedure provide a protocol for selecting the form of production, which begins at the meet-and-confer stage of the lawsuit. Notably, the requesting party is allowed to request the form or forms in which ESI should be produced (usually in a searchable format).16 If the requesting party fails to request a form of production, or the responding party objects to the form requested, the responding party must state the form or forms it intends to use.17 Absent exceptional circumstances, plaintiff’s counsel should insist that the documents be produced in a searchable native format, with metadata intact, which is likely to save cost and time compared to formats that require conversion of the ESI images into load files. Questions regarding form of production should be addressed to a competent IT manager or third-party vendor.

Cost-Shifting Issues. One of the most litigated questions in cases involving electronic data is “who pays?” In many cases, defense counsel will argue that the discovery request is impermissible because it is overly broad, unduly burdensome, or expensive.18 In the ESI context, this is a short-hand reference to “cost shifting,” a concept that acknowledges that the cost of pursuing specifically identified electronic discovery far exceeds any benefit from the search. In Wisconsin, the relevant factors to assess in determining whether cost shifting is appropriate are as follows:

The specificity of the discovery requests;

The quantity of information available from other and more easily accessed sources;

The failure to produce relevant information that seems likely to have existed but is no longer available on more easily accessed sources;

The likelihood of finding relevant, responsive information that cannot be obtained from other, more easily accessed sources;

Predictions as to the significance of the information;

The importance of the issues at stake in the litigation; and

The parties’ resources.19

The effective use of discovery tools can avoid this debate. In cases with significant electronic discovery, it is no longer appropriate to serve blanket e-discovery requests that seek every imaginable document on a particular issue. Targeted, specific discovery requests addressed at retrieval of relevant documents material to the outcome of the litigation are much more defensible. In some cases, the focus of these requests can be refined after taking the deposition of the opponent’s IT representative or third-party vendor.

In e-discovery, it is no longer proper to search for a needle in an electronic haystack. The party seeking the information must specifically tailor the request to need, the likelihood of responsive information, and the cost of production, or be prepared to pay for what he or she is asking for. The party who fails to comply with these directives will often be stuck footing the bill.

Evidentiary Concerns

Given the complexity of ESI, it is easy to forget that the main goal of electronic discovery is to identify, secure, and submit admissible evidence for consideration by the fact-finder. In this respect, ESI is different than traditional, documentary evidence in several important ways.20 A well-planned electronic discovery plan should take these differences into account.

Assuming that confidential and privileged information has been addressed through prior agreement, counsel must be prepared to authenticate ESI. This can be done through properly drafted requests for admissions pursuant to Wis. Stat. section (Rule) 804.11 or witness testimony taken pursuant to a deposition.

Absent such proof, it can be very difficult to authenticate ESI without specific proof that the evidence is what it is being offered for. Unlike paper documents, which are fixed to a tangible medium of expression, ESI reflects computer data that is routinely rearranged by the computer system in question, making it almost impossible to authenticate. To overcome this hurdle, it is necessary to provide evidence of systemic safeguards within the computer itself (password access, hash tags, encryption) that identify the document as being what it is offered to prove. Discovery should be focused on these key features of the opposing party’s computer system when authentication is in doubt.

Electronic discovery offers other evidentiary challenges. While authentication is the most difficult to resolve, questions of relevance, undue prejudice, and hearsay routinely surface when the admissibility of ESI is at issue. If necessary, a comprehensive e-discovery plan will anticipate these evidentiary arguments and lay the foundation for the admissibility of ESI well before trial.

Conclusion

The principles that govern the discovery of electronically stored information are the same as traditional noncomputer evidence. The complexity of electronic data requires the parties to replace the adversarial approach to discovery with one of cooperation, transparency, and common sense. This approach saves money for the parties, avoids unnecessary discovery disputes, and focuses the parties and the court on legitimate, contested issues surrounding the discovery of ESI. In all cases, these goals are advanced by a discovery plan that flows from a thoughtful meet-and-confer process that is grounded in consensus and good faith.

Endnotes

1 Wis. Stat. § 804.09(1).

2 Zubulake v. UBS Warburg LLC, 220 F.R.D. 212, 217 (S.D.N.Y. 2007) (Zubulake IV).

3 Zubulake v. UBS Warburg LLC,229 F.R.D. 422, 432 (S.D.N.Y. 2004) (Zubulake V); Timothy D. Edwards, Spoliation of Electronic Evidence, Wis. Law. (Nov. 2010).

4 Silvestri v. General Motors Corp., 271 F.3d 583, 590 (4th Cir. 2001).

5 See, e.g., Arista Records LLC v. Tschirhart,241 F.R.D. 462 (W.D. Tex. 2006) (imposing a default judgment on defendant after finding that defendant used “wiping” software to erase data); Nursing Home Pension Fund v. Oracle Corp., 254 F.R.D. 559 (N.D. Cal. 2008) (sanctioning defendant with adverse inference at trial); Great Am. Ins. Co. of N.Y. v. Lowry Dev. LLC, Nos. 1:06CV097 LTS-RHW, 1:06CV412 LTS-RHW, 2007 WL 4268776 (S.D. Miss. Nov. 30, 2007) (reducing plaintiff’s burden of proof as spoliation sanction against defendant).

6 See Zubulake V, 229 F.R.D. at 433.

7 Pension Comm. of the Univ. of Montreal Pension Plan v. Banc of America Securities LLC, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4546 at * 15.

8 See Wis. Stat. § 804.01(2)(e)(1)(a)-(f).

9 Mancia v. Mayflower Textile Servs. Co., 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 83470 at *13 (D. Md. 2008).

10 Helmert v. Butterball LLC, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 28964 (E.D. Ark. 2010).

11 Jill Griset & Melissa Laws, Navigating a Case Through E-Discovery (McGuireWoods 2012).

12 Victor Stanley Inc. v. Creative Pipe Inc., 250 F.R.D. 251, 256-57 (D. Md. 2008).

13 National Day Laborer Organizing Network v. U.S. Immigration & Customs Enforcement Agency, 877 F. Supp. 2d 87 (S.D.N.Y. 2012).

14 Jones, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51312 (N.D. Ill. May 25, 2010) (awarding monetary sanctions, imposing an adverse inference, and requiring additional discovery).

15 See Wis. Stat. § 905.03(5); Fed. R. Evid. 502.

16 Wis. Stat. § 804.09(2)(b)(1).

17 Id.

18 See Wis. Stat. § 804.01(3)(a).

19 See Wis. Stat. § 804.01(2) – Supreme Court Note 2010; Timothy D. Edwards, E-Discovery: Who Pays? Wis. Law. (Oct. 2012).

20 See Timothy D. Edwards, Getting Through the Door: The Admissibility of Electronically Stored Information, Wis. Law. (Jan. 2014).